Offerings in water

Everyone

practised their religion in their own particular way, either privately

or

within the local community. Many houses of the Roman period had a

domestic

altar. People would also attend the temple. We are not exactly sure how

people

practised their religion in the Iron Age. We do however know that they

made

offerings at certain cult sites, particularly on rivers and at wetland

sites

such as peat marshes. People would throw weapons and other objects into

the

water. A lot of this type of material has been dredged up at Kessel and

Lith in

the river area, for example. Human bones have even been found here,

some of

which show signs of violence. It is likely they found their way into

the water

as offerings to the gods. Many cult sites have been identified only by

the

unique finds made there. Traces of actual shrines are rare, as they

have been

largely washed away by the water. It is however quite possible that

shrines

existed in the Iron Age. Unfortunately, we do not know how big they

were or

what they looked like, though the many votive offerings found at Kessel

and

Lith, for example, suggest that some shrines may have been fairly large.

Religion and politics

Most of the

open-air shrines excavated to date were situated at a prominent place

in the

landscape, such as the confluence of two rivers or a higher-lying

ridge. They

were relatively small and simple and, as their name suggests, no

building stood

within the enclosure. Many shrines will have been used mainly by the

local

community, though some drew worshippers from far and wide. There was

therefore

a hierarchy among cult sites, which ranged from local to supra-regional

in

importance. The larger cult sites in the Roman period were probably

associated with

a tribal area (which the Romans called a pagus or civitas). They were

part of

the public domain, and thus also of a political and administrative

system. They

were therefore built on common ground, using public funds. The costs of

the

rituals performed by priests and magistrates were also paid from the

public

purse. A priest in a regional cult probably held an official office.

Generally

speaking, Roman rituals will have been the first to reach these

regional cult

sites. From the start of the Roman period, therefore, temples

increasingly

incorporated Roman features, such as a podium or colonnade. The most

common

type of temple in the Roman Netherlands was the Gallo-Roman temple,

whose

square innermost shrine was surrounded by a colonnade. The new temples,

with

their Roman-style architectural features, were symbols of loyalty to

the Roman

authorities and an expression of a desire for full integration into the

Roman

empire. The architecture of the new temples was therefore above all a

political

statement. It was probably also the case that, the more opulent a

temple, the

higher the status and greater the reputation of the deity to whom it

was

dedicated.

Open-air shrines

It

is not

known whether certain buildings or structures would have stood at the

wetland

sites where offerings were made. It is suspected that there were

special

structures, but since the sites were usually on the banks of a river,

any

traces will have largely been washed away. We do however know of a

number of

cult sites on dry land. They were established in the first century AD,

and some

remained in use into the third century. Their form seems to hark back

to the

cult sites of three hundred years previously. They were small open-air

shrines

in the form of a square plot surrounded by a ditch, and sometimes an

embankment, dividing the spiritual world and the ordinary world. Within

the

enclosure, posts stood in a distinctive pattern. Ancient writers also

report

sacred trees at the shrines of the indigenous population. People

brought

offerings of weapons, coins, cloak pins, bracelets, food and drink to

the

shrine. These offerings, which were placed in large pits, have told us

a lot

about the shrines. Such finds are an important indicator of cult sites,

as they

often differ in type and quantity from finds commonly made at

settlement sites.

It

is not

known whether certain buildings or structures would have stood at the

wetland

sites where offerings were made. It is suspected that there were

special

structures, but since the sites were usually on the banks of a river,

any

traces will have largely been washed away. We do however know of a

number of

cult sites on dry land. They were established in the first century AD,

and some

remained in use into the third century. Their form seems to hark back

to the

cult sites of three hundred years previously. They were small open-air

shrines

in the form of a square plot surrounded by a ditch, and sometimes an

embankment, dividing the spiritual world and the ordinary world. Within

the

enclosure, posts stood in a distinctive pattern. Ancient writers also

report

sacred trees at the shrines of the indigenous population. People

brought

offerings of weapons, coins, cloak pins, bracelets, food and drink to

the

shrine. These offerings, which were placed in large pits, have told us

a lot

about the shrines. Such finds are an important indicator of cult sites,

as they

often differ in type and quantity from finds commonly made at

settlement sites.

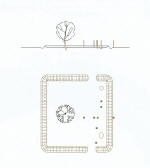

A shrine at a settlement

The

shrine at

Hoogeloon is typical in terms of its shape and structure of the

open-air

shrines found so far in the southern Netherlands, albeit one of the

smallest. It

was a 20.5 x 22.5 m square surrounded by a ditch 50-100 cm wide and

originally

probably 60-130 cm deep. There were two gaps in the ditch on opposite

sides.

Within the enclosure stood two rows of posts and probably also one or

more

trees. Although the finds at the cult site in Hoogeloon differed

somewhat from

the normal votive offerings at other shrines, they were clearly

intended as

offerings. The contents of the pits included deliberately broken

pottery and

iron blades. The pottery, imported from other parts of the Roman

empire, was

very unusual for that period in the Netherlands. The cult site at

Hoogeloon lay

50 m outside the enclosure of the excavated settlement, which in the

second

century grew into a villa-like settlement with a main building in the

Roman

style. The shrine was still in use at the time of the villa. It is not

the only

shrine known to have stood near a villa-like settlement. A small shrine

was

also found at Oss-Westerveld.

The

shrine at

Hoogeloon is typical in terms of its shape and structure of the

open-air

shrines found so far in the southern Netherlands, albeit one of the

smallest. It

was a 20.5 x 22.5 m square surrounded by a ditch 50-100 cm wide and

originally

probably 60-130 cm deep. There were two gaps in the ditch on opposite

sides.

Within the enclosure stood two rows of posts and probably also one or

more

trees. Although the finds at the cult site in Hoogeloon differed

somewhat from

the normal votive offerings at other shrines, they were clearly

intended as

offerings. The contents of the pits included deliberately broken

pottery and

iron blades. The pottery, imported from other parts of the Roman

empire, was

very unusual for that period in the Netherlands. The cult site at

Hoogeloon lay

50 m outside the enclosure of the excavated settlement, which in the

second

century grew into a villa-like settlement with a main building in the

Roman

style. The shrine was still in use at the time of the villa. It is not

the only

shrine known to have stood near a villa-like settlement. A small shrine

was

also found at Oss-Westerveld.

In the

northern provinces, particularly in the towns, temples were also built

according to the Mediterranean tradition. In the harbour of the colonia

in Xanten, just across the

German border, for example, people could attend a large temple that

would not

have looked out of place in one of the Roman towns in Italy. However,

no

temples built in the Mediterranean tradition have yet been found in the

Netherlands, though the two Roman towns on Dutch territory have not yet

been

fully investigated.

New temples

The

most

common type of temple in the Roman Netherlands is known as a

Gallo-Roman temple.

These temples, which were common in the northern provinces, were a

provincial

variation on the classical temple. The Gallo-Roman temple consisted of

a

tower-like chamber – the cella – which housed the idol, and was

therefore the

most sacred part of the temple. A covered colonnade ran around this

chamber.

The temple was not accessible to the faithful, who would pray, make

offerings

and attend rituals at the altar in front of the temple. The altar was

therefore

the most important feature of the temple site, as no rituals could be

performed

without it. The temple and altar were generally in a walled enclosure,

in which

other smaller shrines might also stand. There are several variations on

temple

buildings, distinguished mainly by classical architectural features

such as

columns and a podium. The Gallo-Roman temple in the centre of Elst, for

example, stood on a podium, a classical feature that has been found in

only a

few Gallo-Roman temples. Some temple complexes have two or more

enclosed temples

alongside each other, like the two temples on the Maasplein in Nijmegen.

The

most

common type of temple in the Roman Netherlands is known as a

Gallo-Roman temple.

These temples, which were common in the northern provinces, were a

provincial

variation on the classical temple. The Gallo-Roman temple consisted of

a

tower-like chamber – the cella – which housed the idol, and was

therefore the

most sacred part of the temple. A covered colonnade ran around this

chamber.

The temple was not accessible to the faithful, who would pray, make

offerings

and attend rituals at the altar in front of the temple. The altar was

therefore

the most important feature of the temple site, as no rituals could be

performed

without it. The temple and altar were generally in a walled enclosure,

in which

other smaller shrines might also stand. There are several variations on

temple

buildings, distinguished mainly by classical architectural features

such as

columns and a podium. The Gallo-Roman temple in the centre of Elst, for

example, stood on a podium, a classical feature that has been found in

only a

few Gallo-Roman temples. Some temple complexes have two or more

enclosed temples

alongside each other, like the two temples on the Maasplein in Nijmegen.

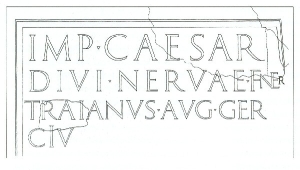

All

these indications of government

involvement suggest the hand of emperor Traianus, who was in power from

AD 98

to 117. It is known that he focused on the development and integration

of the

border provinces, with the aim of achieving stability and firm control.

This

not only required a good infrastructure, but also the development of a

civilian

administration and social stability. It is quite possible that he built

public

buildings in rural areas in an attempt to achieve this. The building of

temples

might have played an important role in the integration of the

population and

the administrative structure of the civitas.

All

these indications of government

involvement suggest the hand of emperor Traianus, who was in power from

AD 98

to 117. It is known that he focused on the development and integration

of the

border provinces, with the aim of achieving stability and firm control.

This

not only required a good infrastructure, but also the development of a

civilian

administration and social stability. It is quite possible that he built

public

buildings in rural areas in an attempt to achieve this. The building of

temples

might have played an important role in the integration of the

population and

the administrative structure of the civitas. In

Empel, just

to the south of the river Maas, the progression from an indigenous

shrine to a

Gallo-Roman temple can be clearly discerned. The temple stood on a

protruding

sandy outcrop, giving it a striking aspect in this landscape sculpted

by the

rivers, with its old gullies and river deposits. The fact that the

Gallo-Roman

temple in Empel had an indigenous predecessor in the first century BC

is

evidenced by the many unique metal objects found there. They include

cloak pins

(fibulae), gold and silver Celtic

coins, bronze belt hooks and fragments of bronze swords. Such finds are

rare in

settlements or gravefields, which strongly suggests that this was in

fact a

cult site. The dates of the finds suggest that the cult site may have

already

been in use in 100 BC, and possibly even earlier. In the early stages

there

were probably no monumental buildings there, and the site is likely to

have

been an open-air shrine at that time. This continued to be the case

until the

Early Roman period (up to c. AD 50), although there do seem to have

been two

18-metre rows of posts oriented east-west during that period. They

probably had

a ritual function, as Early Roman votive offerings have been found

around the

post arrangements. There were several large pits around the northern

row, which

have also yielded remains of a number of metal objects. Parallel to the

northern and southern edges of the river dune (donk) stood several

dense rows of stakes, which may have formed

some kind of perimeter fence. They might also have had a role in water

management at the

In

Empel, just

to the south of the river Maas, the progression from an indigenous

shrine to a

Gallo-Roman temple can be clearly discerned. The temple stood on a

protruding

sandy outcrop, giving it a striking aspect in this landscape sculpted

by the

rivers, with its old gullies and river deposits. The fact that the

Gallo-Roman

temple in Empel had an indigenous predecessor in the first century BC

is

evidenced by the many unique metal objects found there. They include

cloak pins

(fibulae), gold and silver Celtic

coins, bronze belt hooks and fragments of bronze swords. Such finds are

rare in

settlements or gravefields, which strongly suggests that this was in

fact a

cult site. The dates of the finds suggest that the cult site may have

already

been in use in 100 BC, and possibly even earlier. In the early stages

there

were probably no monumental buildings there, and the site is likely to

have

been an open-air shrine at that time. This continued to be the case

until the

Early Roman period (up to c. AD 50), although there do seem to have

been two

18-metre rows of posts oriented east-west during that period. They

probably had

a ritual function, as Early Roman votive offerings have been found

around the

post arrangements. There were several large pits around the northern

row, which

have also yielded remains of a number of metal objects. Parallel to the

northern and southern edges of the river dune (donk) stood several

dense rows of stakes, which may have formed

some kind of perimeter fence. They might also have had a role in water

management at the There

is a lot of evidence to suggest that the temple was dedicated to

the god Hercules-Magusanus, a fusion of an indigenous god and a Roman

demi-god,

to whom many objects were offered at this temple. Many items of

military

equipment have also been found. Hercules Magusanus appears to have

enjoyed

great popularity among soldiers in the Roman army. A bronze plaque

bearing a

votive inscription to Hercules Magusanus not only tells us the name of

the god

venerated at the temple in Empel, but also the name of one of the Roman

army

veterans who made an offering here.

There

is a lot of evidence to suggest that the temple was dedicated to

the god Hercules-Magusanus, a fusion of an indigenous god and a Roman

demi-god,

to whom many objects were offered at this temple. Many items of

military

equipment have also been found. Hercules Magusanus appears to have

enjoyed

great popularity among soldiers in the Roman army. A bronze plaque

bearing a

votive inscription to Hercules Magusanus not only tells us the name of

the god

venerated at the temple in Empel, but also the name of one of the Roman

army

veterans who made an offering here.The most

common form of temple in the Roman Netherlands is the Gallo-Roman

temple. Such

temples – a provincial variation on the classical temple – were fairly

widespread in the northern provinces. Some probably developed from

indigenous

shrines. When a temple was built, most traces of the underlying shrine

will

have been destroyed, though the remaining traces and finds do allow us

to draw

some conclusions about the different phases.

Two temples

In

Elst, in

the heart of Batavian territory, two Gallo-Roman temples have been

excavated in

close proximity to each other. The better-known of the two lies beneath

a

church in the centre of Elst, and its foundations can still be viewed.

It is

one of the largest Gallo-Roman temples currently known, and probably

played an

important role in the organisation of Batavian religion. A second,

smaller

temple has been found in Elst-Westeraam, some 650 metres as the crow

flies from

the temple beneath the church. This second temple was not excavated

until a few

years ago. The robber trenches of an enclosed Gallo-Roman temple were

found.

In

Elst, in

the heart of Batavian territory, two Gallo-Roman temples have been

excavated in

close proximity to each other. The better-known of the two lies beneath

a

church in the centre of Elst, and its foundations can still be viewed.

It is

one of the largest Gallo-Roman temples currently known, and probably

played an

important role in the organisation of Batavian religion. A second,

smaller

temple has been found in Elst-Westeraam, some 650 metres as the crow

flies from

the temple beneath the church. This second temple was not excavated

until a few

years ago. The robber trenches of an enclosed Gallo-Roman temple were

found.

The first

phase of the temple consisted of a wooden cult building erected in AD

10-20 on

the banks of a small, almost dried-up river. It was a two-aisled,

rectangular

building with a temple precinct (temenos)

around it. The entire thing was surrounded by ditches and a palisade of

upright

wooden planks. Remains of these planks have been found in the outermost

of the

two surrounding ditches, and have been dated on the basis of their tree

ring

pattern. After this first phase the building was reconstructed twice in

wood.

The orientation of the building changed during reconstruction. In the

third and

final timber phase (c. AD 70-100) the entrance was eventually situated

on the

west side of the building and surrounding palisade. Interestingly, a

row of

posts found during the excavation suggests that there was also an

open-air shrine

immediately behind the cult building in the third phase.

Rebuilt in stone

The temple was

rebuilt in stone around AD 100. Whereas it had been a two-aisled

building in

the past, the new temple was built in the Gallo-Roman style. Although

the

temple at Elst-Westeraam was smaller than that in the centre of Elst,

it had an

impressive entrance that protruded above the roof of the colonnade.

There was a

pediment, or tympanum, above the entrance, supported by columns larger

than

those found in the rest of the building. The roof of the inner chamber,

the

cella, was higher than that of the surrounding colonnade, as was common

in

Gallo-Roman temples. The temple underwent modifications in the second

half of

the first century, with the addition of a stone extension (an exedra)

against

the southern portico of the temple. The temple still stood in an

enclosed

precinct surrounding by a palisade. On the edge of the site there were

probably

two other shrines with cult images. A well and fourteen small ovens

have also been

found in the temple precinct, offering an insight into the rituals that

were

performed on the temple site. The ovens contained remains of burnt food

(meat

and bread). The temple at Elst-Westeraam was probably abandoned some

time in

the second half of the second century.

Roman foot

Interestingly,

the design of the cult building and surrounding precinct for the second

phase

(from AD 38-39) was based on the Roman foot (pes). This suggests that

Romans or

Roman army veterans were already involved in the building of the temple

at this

early stage.