"When at length they deemed that they were prepared for that purpose, they set fire to all their strongholds (oppida), in number about twelve, their villages (vici), in number about 400 and the rest of their private buildings (aedificia privata); they burnt up all their corn save that which they were to carry with them…" (trans. H.J.Edwards (Loeb edition).

This source clearly shows that, apart from defended urban sites, the infrastructure of Helvetian territory also contained village type settlements as well as what must have been a fairly large number of isolated farms, if the figures given in the text were realistic. Little is currently known about these farms, especially in the period after the Gallic War, mostly because of the difficulties encountered in locating such flimsy late LaTène timber structures, especially on the soils which dominate the study area. The near total lack of evidence for Iron Age predecessors at the sites of better studied Roman farms (villae rusticae) is noteworthy, however, and largely precludes the possibility of site continuity between the late Iron Age and the Roman Empire.

There are exceptions to this rule, notably the partially excavated villa rustica at Messen (Kt.Solothurn) and the farm at Morat/Murten (Kt. Fribourg). Messen's origins seem to have lain with a mid 1st century BC, timber, post building with whitewashed clay walls and enclosure ditches. Morat/Murten produced traces of structures, pits and a cremation, all of which also suggest occupation in the mid 1st century BC. The most impressive current evidence for settlement continuity in Switzerland, however, are features beneath the Roman villa of "Parc de La Grange" in Geneva (Kt. Genève), although this is technically part of Allobrogan territory (Gallia Narbonensis) and so lay just outside the limits of an Upper German study area. Along with several enclosure ditches, which date back to the 2nd century BC, a sequence of three timber post buildings/cill-beam structures have been identified, with simple rectangular ground plans and no discernible internal divisions. They existed from the mid 1st century BC onwards and final alterations took place between 10 BC and 10 AD.

At other villa sites the evidence is limited

to the presence of Iron Age artefacts: mostly small finds such as pottery,

whose date is complicated by the longevity of the indigenous traditions of

shapes and production, which lasted well into the early Roman period. It is

thus hard to decide whether a multangular ditch under the main building of

the villa rustica of Möhlin (Kt.Aargau), whose fill produced late LaTène finds, was really pre-Roman or already early Roman, especially as the timber

buildings of the first securely identifiable Roman settlement were apparently

aligned on the ditch.

At other villa sites the evidence is limited

to the presence of Iron Age artefacts: mostly small finds such as pottery,

whose date is complicated by the longevity of the indigenous traditions of

shapes and production, which lasted well into the early Roman period. It is

thus hard to decide whether a multangular ditch under the main building of

the villa rustica of Möhlin (Kt.Aargau), whose fill produced late LaTène finds, was really pre-Roman or already early Roman, especially as the timber

buildings of the first securely identifiable Roman settlement were apparently

aligned on the ditch.

A case for limited continuation of indigenous building traditions at the start of the Roman occupation can be made for the first phase of the villa of Laufen-Müschag (Kt.Bern). The almost rectangular timber post structure, which was built around 14/20 AD, apparently had wattle and daub walling with clay in-fill and a thatch or shingle roof. Its reconstructed internal division, which was accessed by two double doors, currently has no parallels among the main buildings of fully Roman farms although it is associated with a drain, lined with limestone blocks, which runs to the north-east.

The four roomed house apparently served as a residence for people whose initial sources of income must have included mining and processing the local Iron ore. The old timber building, and a 12 post ancillary building which may have been associated with it, were systematically demolished c. 66/70 AD, possibly just before the completion of the first phase of a new stone main building, whose U-shaped portico intersected the earlier structure.

In as much as the limited state of current research permits such conclusions, it would seem that settlement continuity was equally rare in the territories of the Sequani and Lingones. Possible links to the late Iron Age are usually predicated on pottery evidence, as in the case of the large villa of Lux (Dèp. Côte-d'Or / F), whose origins may date back to the LaTène III period, but no securely datable buildings of this era have yet been identified. Some villas, such as Pont-de-Poitte (Dèp. Jura / F) and Chassey-Lès-Montbozon (Haute Marne / F) may have been founded in the early Augustan period but, again, the extent to which such sites can be considered as the direct successors of the numerous, but largely unexplored, indigenous farms, whose immediate neighbours they often are, remains speculative, if occasionally discussed.

Apart from the few sites with signs of settlement continuity from the late Latène period, a general trend towards the systematic development of Helvetian and Rauracan territory with villae rusticae (i.e. agricultural enterprises) only developed during the first third of the 1st century AD. The fact that this coincides with the establishment of the legionary fortress at Windisch/Vindonissa (Kt.Aargau) in 16/17 AD raises the possibility of a causal link in which the rural development was triggered by the raised demand caused by the permanent military presence. Nothing in the first phase of settlement points to a special relationship with the military, however, or even to a concentration of farms in the Windisch area, as one might have expected.

By the mid 1st century AD, there was still no noticeable change in site distribution and an apparent concentration of settlements in northern Switzerland probably reflects current publication levels rather than historical reality.

During the second half of the 1st century, a further intensification of the settlement pattern can be observed, which is again most noticeable in northern Switzerland. The growth in the number of farms was now particularly marked in the hinterland of the Windisch (Kt.Aargau) legionary base, despite its being almost ignored hitherto. The current state of research would also point to an expansion of the ‘villa landscape’ into the south-eastern Mittelland (central Switzerland) and along the foothills of the Alps. These are topographically less favourable as settlement areas and there is a particularly remote example in the villa of Alpnach (Kt.Obwalden).

By comparison with the waves of settlement over the preceding period, the 2nd century saw a marked drop in the number of newly established villas in the study area, many of which were once again concentrated in northern Switzerland.

Most of the finds from villas in the territory of the Sequani and Lingones have only been published in summary fashion but, here too, at least amongst the better-dated sites, a relatively strong surge of foundations can be seen from as early as the first half of the 1st century. Indeed, in some cases, as outlined above, its origins seem to go back to the Augustan period. Thereafter, however, only occasional foundations are known from the mid to late 1st century, albeit the start dates for most of the villas for which any chronological information at all is available, cannot be refined more closely than that they do date to this century. Almost no sites are known with potential 2nd century foundation dates.

Despite large gaps in our knowledge, we might assume that early 1st century villas in Helvetian and Sequani territory were initially constructed of timber. In some cases, e.g. Wetzikon-Kempten (Kt.Zürich) (founded 50/70AD), the structures could then remain in use into the middle years of the century but, elsewhere, stone construction had come to dominate by this time, and older timber buildings were increasingly being replaced in stone. Such conversions naturally focused on the main building, while the ancillary buildings and flimsy stables frequently continued to use timber. Indeed they were occasionally still being built/rebuilt in this material. A case in point is a timber secondary building with a possible residential function at Aeschi (Kt. Solothurn), which was originally built in the mid 1st century, and only converted to stone at the beginning of the 2nd.

Any clear-cut differentiation between timber and stone construction must, anyway, be regarded with a degree of scepticism. Because, as many of the archaeological remains survive no higher than the bottommost foundation levels, it is often impossible to decide whether the walls that rested on them were of massive, fully stone construction, or just timber-framed structures on stone dwarf walls. That said, there are a few cases where a firm identification is possible: an example being the main building at Alpnach (Kt. Obwalden), founded c. 90/100 AD, where destruction deposits from its initial phase clearly show timber-framed construction.

One peculiar feature of settlement development in the Swiss Mittelland is the initial absence of sites in the area around Windisch and its subsequent rapid development with villas during the second half of the 1st century. It remains unclear, however, whether this, and the contemporary development of topographically less favoured areas, was the results of a planned and carefully managed settlement programme. A further regional phenomenon is a concentration of military brick stamps on villa sites in northern Switzerland, which remains unparalleled in either the German provinces or Raetia.

The most commonly found stamps belonged to the legions stationed at Windisch-Vindonissa: i.e. Legio XXI Rapax, from 45/46-69 AD, and then XI Claudia, from 70-101. In the second half of the 1st century, the bricks were used largely in the rebuilding of older sites, e.g. the villas of Gränichen (Kt. Aargau), Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich), Triengen (Kt. Luzern) and Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich), but they also appear in new foundations. Most sites only produce stamps in relatively small numbers: in the order of 1-10. The villa of Triengen (Kt.Luzern) is thus unusual in that it has so far yielded at least 258 bricks with legionary stamps. Yet even such a small and out-of-the-way site as Alpnach (Kt.Obwalden) had 52 Windisch legionary bricks.

There, thus, appears to have been a link to the military in the supply of building materials to civilian rural settlements, which might hint at so far undefined relationships between the army and the villa occupants. It is possible, for example, that the latter were tenants of military property, perhaps territorium legionis. Nor can it be ruled out that we are seeing a government-led rural development programme in which the military played a supporting role by providing private villa owners with materials, possibly on favourable terms. Some of the production sites, i.e. the brickworks, apparently lay between Hunzenschwil and Rupperswil, east of Aarau (Kt.Aargau) and even new 2nd century foundations, such as the villas at Döttingen (Kt. Aargau) and Koblenz (Kt. Aargau) used such bricks, apparently for the first time.

While the number of new villa foundations was small in the 2nd century, this in no way means that the period left no trace amongst the rural Helvetii and Rauraci. Apart from the change from timber to stone, which continued into the second half of the century (e.g. the main building at Kallnach (Kt.Bern)), there is plentiful evidence for expansion and redevelopment through the period. This is most commonly seen in extensions to the main buildings, along with an increase in the quality of internal fixtures and fittings, including the provision of new mosaic floors, marble veneers and wall paintings. By now, at the latest, we also see a concentration of villas with palatial main buildings developing between the Neusiedler-See and Lac Leman, and these show marked higher living standards by comparison to northern Switzerland.

The proximity of these sites to a number of important centres was probably significant in this context, for example the Helvetian civitas capital at Avenches/Colonia Aventicum (Kt. Vaud), Nyon/Colonia Iulia Equestris (Kt. Vaud), the large vicus at Lausanne/Lousonna (Kt.Vaud) and the civitas capital of the Allobrogi at Geneva/Genava (Kt. Genève) on the western end of Lac Leman.

Our knowledge of the villas’ early phases still remains full of gaps and the settlements’ original start dates often have to be deduced from small finds, especially pottery. Likewise, we are hampered by the limited methodology used in older excavations, some of which date back to the 18th and 19th centuries. Excavations have often only covered parts of the farmyard and adverse soil conditions have made it difficult to see whether easily recognisable stone buildings were preceded by timber phases in Switzerland, and thus mirror the situation elsewhere. As a result, such features are known only rarely, but they have come to light at:

- Buchs (Kt. Zürich).

- Dietikon (Kt. Zürich).

- Laufen (Kt. Bern).

- Le Landeron (Kt. Neuchâtel).

- Möhlin (Kt. Aargau).

- Morrens (Kt. Vaud).

- Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich).

- Triengen (Kt. Luzern).

- Vallon (Kt. Fribourg).

- Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich).

Usually, the surviving features include sections of wall slots or postholes from timber buildings, and sometimes parts of a farm’s enclosure ditch. With the exception of villas such as Laufen (Kt.Bern), the residential buildings were usually of cill-beam construction, whilst farm buildings are also known to have used posts.

The reconstruction of the villa at Vallon (Kt.Fribourg), which was built at the beginning of the 1st century AD, shows that such cill-beam houses were hard to distinguish from stone buildings, once their timber framing had been plastered.

Sadly, the remains of the sites listed above are all too fragmentary to allow the reconstruction of a complete early farm and, under those circumstances, the best available impression derives from features seen at the villa of Neftenbach (Kt.Zuerich). Here, the first main house was built around 30AD, inside the area of a later stone built villa, and its orientation was copied by all its later successors. It was a rectangular cill-beam structure, with wattle-and-daub in-fills and apparently completely plastered walls. The remains of roof tiles and the presence of eaves drips along the two narrow sides, suggest a hipped roof, possibly covered with shingles. The front and one of the narrow sides had porticos. Inside, two equal sized rooms were identified, one of which preserved fragments of wall painting. Interestingly, a small slot for a fence or hedge (double in some stretches), which approached the main house at right angles, appears to have continued the dividing line between these rooms and this may be the first hint that both the main building and the farmyard as a whole were divided into a working section (pars rustica) and a residential area (pars domestica). Northeast of the main building, inside the hypothetical pars rustica, a simple post-built ancillary building was excavated, whose function seems to have been economic, and the open area between the two was at least partially gravelled. The water supply was provided via a timber pipe, which tapped spring water at a well house and led it to the northwest corner of the main house. A second water pipe was found close to the ancillary building.

Indications of a farm enclosure are only known from phase 2 onwards. It took the form of a small hedge or fence slot, surrounding a rectangular area, and slots and posts suggest the existence of a gate. The beginning of this phase was marked by the destruction of the main house by fire, and its apparently immediate replacement. The new building lay slightly further to the west and was once again a plastered and painted timber framed structure. The cill-beams no longer sat directly on the soil, however, but were supported on low dwarf walls. The ground plan, fronted by a portico with two protruding corner rooms, was already that of the later winged corridor-villa. This is a common type amongst stone residential buildings on villas all over the north-western provinces and discontinued the supposed accommodation of residential and service functions under a single roof that was seen in phase 1. A gravel path with flanking ditches led directly to the front of the main building and gave access to the whole of the fairly large farm area via possible branches. There were five, post-built ancillary buildings, but their distribution does not appear to conform to any discernible pattern. There is also no indication of continued subdivision of the farmyard, but a total of nine cremations, found close to the enclosure, can be attributed to this period. The settlement’s water supply continued to be provided by the timber well house and piping of the preceding period, which was indeed extended, but a sewer, which now ran from the main building, might suggest an additional water supply. During the course of the second timber phase, the first stone building on the site, a free-standing bath block, was constructed, northwest of the main house, and a larger scale redevelopment of the villa in stone began in the 80s.

A villa’s stone phases usually give us the best impression of its composition and structure, although even here comparatively little is yet known about their dimensions. The main house frequently stands out because of its associated masses of stone debris, whilst the robustly constructed bathhouse is often better preserved. As a result, either or both may be recognised and targeted by partial excavations. The flimsier ancillary buildings thus tend to be far less well understood. Large-scale, research-led area excavations on villas, such as those at Orbe (Kt.Vaud), remain the exception and it is more common for the size of the farmyard to be established by digging small trial trenches in the vicinity of known structures, or just by analysing the topography.

Two basic patterns of villa design can be distinguished in the north-western provinces, especially with regards to their component structures:

a) ‘Streuhof’ plan

b) Axial plan

With ‘Streuhof’ plans, the main house and ancillary buildings are distributed over the farmyard in such a way that no meaningful layout concept is detectable. There is little evidence for axiality within the complex, or for a clear separation between the pars urbana and pars rustica (i.e the residential and farming areas). This need not preclude the existence of a more or less rectangular enclosure, but even this cannot be found in all cases.

Within the study region ‘Streuhöfe’ are usually small to medium sized farms and examples include:

- Alpnach (Kt. Obwalden).

- Boécourt (Kt. Jura).

- Ferpicloz (Kt. Fribourg).

- Hüttwilen (Kt. Thurgau).

- Langendorf (Kt. Solothurn).

- Laufen (Kt. Bern).

- Maisprach (Kt. Basel-Land).

- Olten, "Im Grund" (Kt. Solothurn).

- Uetendorf (Kt. Bern).

- Wiedlisbach (Kt. Bern).

- Zurzach(?) (Kt. Aargau).

The outstanding examples of this villa type in the area of the Sequani and Lingones, are the villas of Tavaux (Dép. Jura / F) and, perhaps, Selongey (Dép. Côte-d'Or / F).

Axial designs were oriented on the pars urbana, which was itself centred on the main residence. Its showpiece façade provided the point on which the lines of most of the buildings, enclosure walls and the main access roads were aligned. This resulted in a certain level of symmetry amongst the pars rustica structures, although this does not necessarily mean that every building had its mirror image. One can often differentiate between designs based on the long axis, where the pars urbana was attached to the narrow side of a more or less rectangular courtyard, and short axis designs, where the residential area can be found along one of the long sides. One characteristic is a strict separation of the residence from the pars rustica, and this was frequently reinforced by walls or screening buildings. Moreover, the main residence did not necessarily lie on the same alignment as the farm buildings. It was often slanted away slightly from the farm’s main axis. Axial arrangements predominated in the study region and examples include i.a:

- Biberist (Kt. Solothurn).

- Buchs (Kt. Zürich).

- Colombier (Kt. Neuchâtel).

- Dällikon (Kt. Zürich).

- Dietikon (Kt. Zürich).

- Liestal (Kt. Basel-Land).

- Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich).

- Oberentfelden (Kt. Aargau).

- Orbe (Kt. Vaud).

- Vicques (Kt. Jura).

- Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich).

- Yvonand (Kt. Vaud).

These are all large farms (in terms of area covered)

Similar villas can be found in the territory of the Sequani, for example at Vitreux (Dép. Jura / F), and amongst the Lingones, as at Lux (Dép. Côte-d'Or / F).

These apparent differences in the basic design of the settlements grouped together here as villas, or ‘villae rusticae’, are reflected equally in both their size and architecture. At the bottom of the scale we find farms, such as Boécourt (Kt. Jura), which had a simple residence, one or two ancillary buildings and a farmyard of up to 3ha and which could probably have been worked by a family-sized group.

Medium sized villas would have demanded much higher staff levels, for example the 4.5ha farm of Langendorf (Kt. Solothurn), which sports a further residential building, as well as its main residence and ancillary buildings. Estimates suggest a population of c. 50 people, including the family of the landowner or tenant, dependent families and/or agricultural labourers (cf. amongst others Schucany 1999, 92).

The difference between these sites and the larger estates was probably fluid and, in all likelihood, it was related, above all, to the number of dependents and the concomitant social stratification within the farm. This could be expressed in an increasing separation between the impressively developed residence of the estate owner, the pars urbana, and the farm itself, the pars rustica. The latter contained both farm buildings in the strict sense, and ancillary buildings with residential quarters, and the latter could match the size and architecture of smaller villas’ main houses. The population of the villa at Biberist (Kt.Solothurn), which had an area of c. 5.5 ha, has been estimated at c. 120.

We also need to consider the actual built area, i.e. the capacity of the buildings, and it is perfectly conceivable that Orbe (Kt.Vaud), the villa with the largest farmyard currently known in Helvetian territory (at 400 x 400m (16ha)), housed several hundred people. It is not without reason, therefore, that similar sites, such as the villa at Lux (Dép. Côte-d'Or / F), in the area of the Lingones, have occasionally been described as ‘vici’. For they can indeed resemble such settlements, at least with regard to their infrastructure, which apart from the residential buildings contained, workshops, stables and sanctuaries.

The ‘basilican’ type refers to houses that contained a long rectangular core, often constructed as a three aisled hall. The most impressive Swiss example is the mid 1st century main house at Hölstein (Kt. Basel-Land). But even impressive residences, such as the much-extended main building at Winkel-Seeb (Kt.Zürich), appear to have developed from a basilican plan with porticos, which can first be identified in an early stone phase of the mid 1st century.

The "Zentralhof" type refers to structures, whose rooms were arranged in strip-like wings around a central courtyard. The alternative term ‘Peristyle-villa’ is sometimes used, although it remains debateable whether these were really open courtyards or whether some, at least, may have been central halls. Swiss examples are known i.a. from Bennwil (Kt. Basel-Land) and Triengen (Kt. Luzern) (n.b: while these villas do have a central courtyard, they are substantially smaller than the ‘courtyard villas’ of Britain and should not be confused with them).

The most common architectural type encountered in Helvetian and Rauracan main buildings are the so-called ‘portico-villas’ or ‘corridor-villas’, whose rooms were mostly accessible via an ostentatious portico at the front of the building. On sloping ground, in particular, these were frequently reached by a central perron (freestanding staircase) and they were commonly underpinned by a covered walk (crypto-portico).

The terms "portico-villa" or "corridor-villa" cover several sub-groups. At its most simple, the portico across the front of the building sometimes turned to cover its narrow sides as well. This arrangement can be found at large houses, such as the third (probably) extension of the villa at Meikirch (Kt.Bern) (dated c. 200 AD). It is equally common on smaller sites, however, including (i.a.) the first (Flavian) main building at Orbe (Kt. Vaud), and both stone house periods at Schupfart (Kr. Aargau): although the latter site only had the corner room added to its portico during the second period.

The most common variant in the study area is the so-called ‘winged corridor-villa’. Here the portico is set back between two corner rooms which project from the rest of the house, although there is a rarer type with only one protrusion. This type can be seen at smaller sites, such as Bellikon (Kt.Aargau), Grenchen (Kt.Solothurn), Laufen (Kt.Bern) and Lengnau (Kt. Aargau), as well as at palatial villas such as Buchs (Kt. Zürich) and Worb (Kt. Bern). The porticos usually run straight but, depending on the degree to which the corner rooms project, they can also turn to form a U-shape.

U-shaped porticos are more characteristic of the third variety of winged corridor-villas, which is largely restricted to large sites. Here, the corner rooms are extended to form proper wings, so that in combination with the villa’s main body, a tripartite corridor house is created. Not uncommonly the ends of the wings were linked by a further portico, or attach themselves to the walls of the villa rustica (be it the dividing wall or the estate enclosure wall). This creates a courtyard in front of the villa’s main façade (thus explaining the English term ‘courtyard villa’ for this type, quite different from the ‘Zentralhof’ type discussed above).

The villa of Orbe (Kt.Vaud) has an unusual architectural plan, in which the courtyard was divided in two by a double central portico. One was framed by Tuscan columns, the other by Corinthian, and each of the resulting courtyards had a decorative fountain at its centre.

As suggested by the preceding examples, some villas show a remarkable level of luxury in their interior decoration. This is by no means restricted to the palatial sites, and, with certain gradations, the main buildings of Helvetian and Rauracan villas tend to be fairly sumptuously equipped by comparison with other parts of the German and Raetian provinces. For example, in addition to mono or polychrome painted walls, figural wall paintings are found, not just at large residences, such as Buchs (Kt. Zürich) and Meikirch (Kt. Bern), but also at smaller sites, such as Wetzikon-Kempten (Kt. Zürich), Bellikon (Kt. Aargau) and Hölstein (Kt. Basel-Land). Moreover, these are not necessarily ‘provincial’ in design, as is documented by wall decorations in the Third Pompeian style from the villas of Commugny (Kt. Vaud) and Yvonand (Kt. Vaud).

In addition to wall paintings, quite a few sites, e.g. Buchs (Kt.Zürich), have provided evidence for paving stones or wall veneers (including figural relief decorations) in marble or Jura limestone.

Opus sectile wall decorations and floors are occasionally found, as at Buix (Kt. Jura) and Orbe (Kt. Vaud), which join with the numerous mosaics found in Swiss villas to complete an optical impression of the villas’ interior decor.

In all, 49 of the 109 villas found in the Swiss part of Germania Superior have provided evidence for mosaic floors and, if we take into account the poor preservation of some sites and the small scale of many excavations, the original percentage seems likely to have been even higher. The patterns range from geometrical black-and-white mosaics, to colourful floors with numerous figured scenes. So far, however, the surviving mosaics come almost exclusively from later alterations of the later 2nd and early 3rd centuries. In larger residences mosaics can be found in reception rooms, living quarters and porticoes whilst, at the smaller sites, they appear to be concentrated in the bath suite. The same phenomenon applies equally clearly to wall decorations, and especially to cladding with Jura limestone or marble slabs.

The baths were sometimes the first stone building on a site and were often also the first to see hypocausted heating systems installed. Indeed, at smaller houses this luxury was normally restricted to the baths, which were themselves often added or inserted later, e.g. Bellikon (Kt. Aargau) oder Hölstein (Kt. Basel-Land). Medium sized and larger villas, by contrast, could have hypocausts in some of the rooms in the living quarters, especially after 2nd century alterations. Helvetian and Rauracan bath buildings could be either stand-alone structures or integrated into the main building, and baths that were initially separate were sometimes linked to the main residence during later extensions, by wings or porticos.

Integrated baths were rather more common (by a ratio of 3:2), which is hardly surprising given the reduction of work involved in inserting or attaching one or two bathing rooms to an existing house, rather than creating a separate building. In some cases, however, both types are present. At Orbe (Kt.Vaud), for example, a very large bath suite in the later residence replaced the separate baths of its predecessor, whilst at Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich), a separate bath building next to the villa’s east wing coexisted for some time with an integrated bath in the west wing. Further examples are known, i.a. from Buchs (Kt. Zürich), Colombier (Kt. Neuchâtel), Kloten (Kt. Zürich) and Oberweningen (Kt. Zürich) and, in the last two cases, the integrated baths were apparently inserted in later phases to supplement existing detached blocks.

Bath and villa water supplies could be provided by streams, aqueducts or wells. Biberist (Kt. Solothurn) and Dietikon (Kt. Zürich), i.a, had streams crossing the farms, whilst aqueducts are known at Orbe (Kt. Vaud) and Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich). Neftenbach also had a wooden pipeline in its early phases, which supplied water from a nearby spring, and this was apparently later replaced by a 1.5 km long stone conduit.

Deep wells are relatively rare on Helvetian and Rauracan villas. One possible example at Laufen (Kt.Bern), had a stone lining sitting on a rectangular wooden catchment box, 5m below the surface. On the other hand, a pure stone example, built of river cobbles and rounded stones, has been excavated at Winkel-Seeb (Kt.Zürich). Here, the 6m deep well was integrated into a sophisticated well house, which was placed centrally in the pars rustica. It sat in front of the dividing wall to the pars urbana and thus directly in front of the main residence. The surviving remains suggest a tower-like structure, where the water was raised to the upper storey (possibly with mechanical lifting gear) from where a pressurised pipe led water to the house. To achieve this effect, the local topography requires a building over 9m high.

The same ancillary building was often used as both workshop and living quarters, as is demonstrated by three farm buildings found side-by-side along the north-eastern enclosure wall at Dietikon (Kt.Zürich). Each of these (10-10.5 x 9m) single storied stone buildings originally had a post-built internal division that was later replaced by a light wall on shallow foundations. Postholes, slots and slight foundations also suggest fronting porticoes and further attached or freestanding structures. In the middle of the three (A), normal domestic refuse from pits and levelling layers, plus a neonatal burial just outside, suggest living quarters. But metalworking tools, iron ingots, moulds, crucibles and a further (smithing?) hearth, found in and around the house, imply that iron and copper-alloy working also took place. It is not clear if this workshop/residence belonged together with the neighbouring building to the north (L), but the finds from the latter would suggest that it served solely as a smithy.

To the south of building A, building B was again subdivided into a larger (apparently residential) room with a central fireplace, and a narrower workshop area with a separate external entrance. The entrance was blocked by a smoke house in a later phase, whilst the rear part of the room, which was now separated, received a mortar floor below which two neonatal burials were found. In the northwest corner, a flimsily built extension probably served as a toolshed or wagon shelter, and a much smaller shed on the southeast side had a pig buried just metres away from it. Finds of carpentry and metalworking tools, horse harness and wagon fittings underline the residents’ occupations as craftsmen and stockmen, but other finds illustrate their private lives. These include coins, pottery fragments, furniture, box fittings, a chest fitting, a roasting spit, melon beads, a brooch, a ring, a mirror, toiletry equipment, a spindle whorl and a bronze statue base with the remains of soldering. Similar evidence for mixed usage is known from other buildings with similar ground plans at Dietikon (Kt. Zürich), along with single room structures along the enclosure wall at Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich). The same combined usage is also known from more complex workshop and residential buildings. For example, the large smokehouse and pottery kiln in Building B at Winkel-Seeb (K. Zürich) could be mentioned, or the bronze-casting pit in the large house and courtyard structure 60 at Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich). Other evidence for crafts, apart from normal metalworking, includes iron ore processing, as at Laufen (Kt.Bern) and, more frequently, the production of coarseware, bricks and tiles. Tile kilns were in use at Triengen (Kt. Luzern), Vicques (Kt. Jura) and possibly even Laufen (Kt. Bern). The kiln at the latter site is securely identified, as is that at Obfelden (Kt. Zürich), whilst at Vallon (Kt. Fribourg) there is some evidence for the exploitation of local potting-clay pits. Such production sometimes exceeded the mere provision of the villa’s own needs. For example, pottery from the abovementioned workshop at Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich) has also been found on others sites in the area.

The villas’ agricultural production is much harder to identify than these obvious craft activities and, in contrast to agricultural tools, harness fragments for draft animals and the remains of butchering amongst the finds assemblages, a farm building’s architectural remains only rarely offer secure indications of its use.

Four corn driers were found in a single building (H) at Dietikon (Kt.Zürich), and it is also worth mentioning a stone, hall-like structure at Biberist (Kt.Solothurn), whose floor was raised on pillars to improve air circulation and which was thus, without doubt, a granary. This had residential structures and workshops in its vicinity, along with further remains, which might represent cattle pens or light stables/animal sheds, and so it is possible to reconstruct a small part of the villa with some confidence.

The exact purpose of most hall-like structures (e.g. buildings C and D in the pars rustica of Winkel-Seeb, and an ancillary building at Lauffen (Kt.Bern)), remains unresolved. Depending on the width of their gates they are usually assumed to be barns, stables, byres or wagon sheds.

A partially excavated stone building at Dällikon (Kt.Zürich) produced finds indicative of a sanctuary: including globular bowls, several incense burners and a fragment of figural lamp. Elsewhere, it is primarily the ground plan, coupled to a lack finds whose position and composition would be thought typical for residential quarters or workshops, which suggests such an interpretation. The central room of one building at Orbe (Kt.Vaud) had an apse in the narrow wall facing the entrance, along with couch foundations along the long walls: both of which are clear signs of a mithraeum.

By contrast, the Neftenbach (Kt.Zürich) structure is square with a central foundation for a possible cult statue, whilst the sanctuary at Yvonand (Kt.Vaud) and two securely identified ritual buildings in the pars rustica at Dietikon (Kt.Zürich) had the central cella and rectangular portico, typical of Gallo-Roman temples. Moreover, in the 3rd century, what may originally have been a small podium temple was located in the pars urbana at Dietikon, a short distance from the front of the main building. There were also small chapel-like ancillary structures accompanying both one of the Dietikon temples (G) and the sanctuary at Yvonand (Kt. Vaud).

The remains of a possible source sanctuary, including the springhead, a bathing pool, a house altar and the remains of columns, were found to the west of the main building at Liestal (Kt.Basel-Land) and, apart from the mithraeum at Orbe (Kt.Vaud), this tentative identification provides the only pointer to the cults practised in villa owned sanctuaries, and their regional importance. It is noteworthy, however, that the largest temple (G) at Dietikon (Kt.Zürich) was rebuilt after the villa’s large-scale destruction during the Germanic invasions of the middle and third quarter of the 3rd century. It then continued in use until the mid 4th century, whilst the main building and most of the other villa structures lay in ruins. It is even possible that limited continuation of some of the pars rustica ancillary buildings and a few rooms within the ruins of the main house, might be linked to the continuance of cult rituals, which may have been of regional importance. Alternatively, it is possible that former residents of the pars rustica might have continued the villa’s farming activity, if on a much-reduced scale.

One characteristic of villas in the north-western provinces was an enclosure fence, hedge, ditch or wall around the farmyard buildings. Relatively little is yet known about such enclosures on the small to medium sized villas of Helvetian and Rauracan territory: possibly thanks to incomplete research on the sites. We do know of lengths of palisade at Laufen (Kt Bern), however. These had stone-choked posts set in a trench, and the alignment of the known sections suggests a rectangular enclosure. Elsewhere, ditched enclosures are known, for example at the small villa of Boécourt (Kt.Jura) and the medium-sized site at Triengen (Kt. Luzern). In both cases these were later replaced by stone walls, and similar walls have been found at other small villas. In as much as our incomplete understanding of such walls allows an opinion, these enclosures just formed boundaries around the whole farmyard, with no internal divisions between the residential and agricultural parts of the site. The large axial villas may have operated differently, however. As with the previous examples, the boundaries at Buchs (Kt. Zürich), Dietikon (Kt. Zürich) and Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich) began as ditches or double gullies. These were later replaced by walls but, as well as just enclosing a rectangle, an internal dividing wall then separated the site into a pars rustica and a pars urbana. The farmyard could be either attached to the pars urbana, as at Neftenbach (Kt.Zürich) and Winkel-Seeb (Kt. Zürich) or, as at Orbe(Kt.Vaud) and perhaps Biberist (Kt. Solothurn), it could surround the residential area on more than one side. Access to both parts of the villa was sometimes gained via impressive gates, or even freestanding gatehouses: as is the case with the pars urbana at Neftenbach (Kt. Zürich) and the farmyard at Vicques (Kt.Jura).

The main house was usually a largely freestanding structure, but many other buildings (especially in the pars rustica) were integrated in such a way that the enclosure wall formed one of their own walls. Such buildings can be found both inside the wall, as at Dietikon (Kt. Zürich ) and Oberentfelden (Kt. Aargau), or outside it and some, as at Liestal (Kt.Basel-Land) and Yvonand (Kt.Vaud), could even straddle it.

It is not known whether additional, outer boundaries existed in these cases, possibly formed by hedges or the like. But sites such as Neftenbach (Kt.Zürich) and Vicques (Kt.Jura) have produced walled annexes, and so demonstrate that further boundaries and enclosures can be expected outside a villa’s core area.

Graves are also known from inside the farm enclosure at Neftenbach (Kt.Zürich) and, during its second timber phase (mid 80s of the 1st century AD), more dead were buried in three different locations close by. To judge from the eight simple cremations, however, these are unlikely to have been members of the owners’ family and they were more probably dependent labourers. The two south-eastern groups show some reference to the ancillary buildings, but the north-western group is well removed from any known structure. The contemporaneity of the graves of this group, and suggestions of a double burial, raises the possibility that the deceased may have fallen victim to disease. Burials within villa walled enclosures remain rare, however, apart from these exceptional cases and, slightly more common instances of infant burial, such as those at Dietikon (Kt.Zürich) and Neftenbach (Kt.Zürich). Sadly, external graves have also only rarely been documented, and examples such as a 2nd/3rd century inhumation found 1200m from the main residence at Worb (Kt. Bern) raise the question of how far even these might be related to the villa. Further indications of external cemeteries are known i.a. from Obfelden (Kt. Zürich) and Orbe (Kt.Vaud), and may have continued into the early Middle Ages.

Christian Miks

Agustoni 1992 C. Agustoni, La villa de Morat/Combette. In: Le passé apprivoisé. Archéologie dans le canton de Fribourg. Exposition Fribourg, 18. septembre - 1er novembre 1992 (Fribourg 1992) 110f.

Agustoni u.a. 1996 C. Agustoni / M. Fuchs, Colonnes et balustrades peintes à Morat. In: Fuchs 1996, 10f..

Ammann-Feer 1937 P. Ammann-Feer, Eine römische Siedlung bei Ober-Entfelden. Argovia 48, 1937, 139ff..

Bacher 1990 R. Bacher, Das Badegebäude des römischen Gutshofes Wiedlisbach-Niderfeld. Arch. Bern 1, 1990, 165ff..

Banateanu u.a. 1996 D. V. Banateanu / M. Golubic / F. Saby, La villa gallo-romaine de Vallon. In: Fuchs 1996, 27ff..

Barbet 1997 G. Barbet / P. Gandel, Chassey-Lès- Montbozon (Haute-Saône) - Un etablissement rural gallo-romain. Annales Littéraires de l'Université de Franche-Comté, 627. Série archéologie n° 42 (Paris 1997).

Bénard u.a. 1994 J. Bénard / M. Mangin / R. Goguey / L. Roussel, Les agglomérations antiques de Côte-d'Or. Annales Littéraires de l'Université de Besan on, 522. Série archéologie n° 39 (Paris 1994).

Blondel u.a. 1922 L. Blondel / G. Darier, La villa romaine de la Grange, Genève, Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 24, 1922, 72ff..

Boisaubert u.a. 1992 J.-L. Boisaubert / M. Bouyer / T. Anderson / M. Mauvilly / C. Agustoni / M. Moreno Conde, Quinze années de fouilles sur le tracé de la RN1 et ses abords. Arch. Schweiz 15, 1992, 41ff..

Bonstetten 1858 G. von Bonstetten, Die Merkur-Statuette von Ottenhusen, Kt. Luzern. Der Geschichtsfreund 14, 1858, 100ff..

Bouffard 1942 P. Bouffard, Ein römisches Pflugeisendepot aus Büron. Ur-Schweiz 6, 1942, 71ff..

Bosch 1930 R. Bosch, Die römische Villa im Murimooshau (Gemeinde Sarmenstorf, Aargau). Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 32, 1930, 15ff..

Bosch 1958 R. Bosch, Die römische Villa im Murimooshau (Gemeinde Sarmenstorf). Heimatkde. aus dem Seetal 32, 1958, 3ff..

Bratschi u.a. 1982 S. Bratschi / P. Corfu / A.-P. Krauer, Le matériel archéologique recueilli dans la villa de Cuarnens. Etudes de Lettres, Université de Lausanne No 1, 1982, 77ff..

Bujard u.a. 2002 J. Bujard / J.-d. Morerod, Colombier NE, de la villa au château - L'archéologie à la recherche d'une continuité. In: Windler u.a. 2002, 49ff..

Châtelain 1976 H. Châtelain, La villa romaine de Commugny. Helvetia Arch. 7, 1976, 39ff..

Colombo 1982 M. Colombo, La villa gallo-romaine d'Yvonand-Mordagne et son cadre rural. Etudes de Lettres, Université de Lausanne No 1, 1982, 85ff..

Courvoisier 1963 J. Courvoisier, Les Monumnets d'art et d'histoire du canton de Neuchâtel 2 (Basel 1963).

Degen 1957 R. Degen, Eine römische Villa rustica bei Olten. Ur-Schweiz 21, 1957, 36ff..

Degen 1957 R. Degen, Fermes et villas romaines dans le canton de Neuchâtel. Helvetia Arch. 11, 1980, 152ff..

Demarez 2001 J.-D. Demarez, Rèpertoire archéologique du canton Jura du 1er siécle avant J.-C. au VIIe siècle après J.-C. Cahier d'Archéologie Jurassienne12 (Porrentruy 2001).

Deschler-Erb 1999 E. Deschler-Erb, "Made in Switzerland" Kasserollen vom Typ Biberist. Arch. Schweiz 22, 1999, 96ff..

Deschler-Erb 2003 E. Deschler-Erb, Une applique de bride découverte à Biberist SO. A propos d'un nouveau type. Jahrb. SGUF 86, 2003, 186ff..

Drack 1943 W. Drack, Die römische Villa von Bellikon-Aargau. Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 5, 1943, 86ff..

Drack 1945 W. Drack, Das römische Bauernhaus von Seon-Biswind. Argovia 57, 1945, 221ff..

Drack 1950 W. Drack, Die römische Wandmalerei der Schweiz. Monographien zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Schweiz 8 (Basel 1950)

Drack 1959 W. Drack, Neue Entdeckungen zu römischen Gutshöfen im Kanton Zürich 1958. Ur-Schweiz 23, 1959, 30ff..

Drack 1964 W. Drack, Das römische Brunnenhaus bei Seeb (Gem. Winkel, Kt. Zürich). Ur-Schweiz 28, 1964, 99ff..

Drack 1964/1967 W. Drack, Der römische Gutshof bei Seeb. Provisorischer Führer (Zürich 1964 und 1967).

Drack 1967 W. Drack, Die Funde aus der römischen Villa von Grenchen-Breitholz und ihre Datierung. Jahrb. Solothurn. Gesch. 40, 1967, 445ff..

Drack 1969/1981 W. Drack, Der römische Gutshof bei Seeb. Archäologische Führer der Schweiz 1 (Basel 1969 u. 1981).

Drack 1970 W. Drack, Der römische Gutshof Seeb. Helvetia Arch. 1, 1970, 38ff..

Drack 1974 W. Drack, Die römische Wandmalerei von Buchs. Arch. Korrbl. 4, 1974, 365f..

Drack 1975 W. Drack, Die Gutshöfe. In: Ur- und frühgeschichtliche Archäologie der Schweiz 5: Die römische Epoche (Basel 1975) 49ff..

Drack 1976 W. Drack, Die römische Kryptoportikus von Buchs ZH und ihre Wandmalerei, Archäologische Führer der Schweiz 7 (Basel 1976).

Drack 1978 W. Drack, Ruine eines römischen Herrenhauses in Obermeilen. Heimatbuch Meilen 1978, 5ff..

Drack 1980 W. Drack, Das römische Herrenhaus von Ottenhusen in der Gemeinde Hohenrain LU. In: Festschrift G. Boesch (Schwyz 1980) 113ff..

Drack 1990 W. Drack, Der römische Gutshof bei Seeb, Gem. Winkel. Ausgrabungen 1958-1969. Berichte der Zürcher Denkmalpflege, Archäologische Monographie 8 (Zürich 1990).

Drack 1986 W. Drack, Römische Wandmalerei aus der Schweiz (Feldmeilen 1986).

Drack u.a. 1988 W. Drack / R. Fellmann, Die Römer in der Schweiz (Stuttgart-Jona 1988).

Dubois u.a. 2001 Y. Dubois / C.-A. Paratte, La pars urbana de la villa gallo-romaine d'Yvonand VD-Mordagne. Rapport intermédiaire. Jahrb. SGUF 84, 2001, 43ff..

Ebnöther 1991 C. Ebnöther, Die Gartenanlage in der pars urbana des Gutshofes von Dietikon. Arch. Schweiz 14, 1991, 250ff..

Ebnöther u.a.1993-1994 C. Ebnöther / J. Leckebusch; Siedlungsspuren des 1.-4. Jh. n.Chr. in Wetzikon-Kempten. Archäologie im Kanton Zürich - Ber. Kantonsarch. Zürich 13, 1993-1994, 199ff..

Ebnöther 1995 C. Ebnöther, Der römische Gutshof in Dietikon. Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 25 (Zürich-Egg 1995).

Ebnöther u.a. 1996 C. Ebnöther / J. Rychener, Dietikon und Neftenbach ZH: Zwei vergleichbare Gutshöfe?. Jahrb. SGUF 79, 1996, 204ff..

Ebnöther u.a. 2002 C. Ebnöther / J. Monnier, Ländliche Besiedlung und Landwirtschaft. In: Flutsch u.a. 2002, 135ff..

Eggenberger u.a. 1992 P. Eggenberger / L. Auberson, Saint-Saphorin en Lavaux. Le site gallo-romain et les édifices qui ont précédé l'église. Cahiers d'Archéologie Romande 56 (Lausanne 1992).

Engel 1971 J. Engel, Une villa romaine à Marly, Fribourg. Helvetia Arch. 2, 1971, 65ff..

Ettlinger 1946 E. Ettlinger, Die Kleinfunde der römischen Villa von Bennwil. Tätigkeitsberichte der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Baselland 16, 1946, 57ff..

Ewald u.a. 1978 J. Ewald / A. Kaufmann-Heinimann, Ein römischer Bronzedelphin aus Munzach bei Liestal BL. Arch. Schweiz 1, 1978, 23ff..

Felka u.a. 1982 H. Felka / F. Loi-Zedda, La villa gallo romaine de Cuarnens. Etudes de Lettres, Université de Lausanne No 1, 1982, 49ff..

Fellmann 1949 R. Fellmann, Neues vom "Römerbad" in Zofingen, Ur-Schweiz 13, 1949, 23ff..

Fellmann 1950 R. Fellmann, Ein Tischfuß aus der römischen Villa von Rekingen. Ur-Schweiz 20, 1956, 42ff..

Fellmann 1950 R. Fellmann, Die Gallo-römische Villa rustica von Hinterbohl bei Hölstein. Baselbieter Heimatb. 5, 1950, 28ff..

Ferdière 1988 A. Ferdière, Les campagnes en Gaule romaine. 1. Les hommes et l'environnement en Gaule rurale (52 av. J.-C. - 486 ap. J.-C.) (Paris 1988).

Fetz u.a. 1997 H. Fetz / Ch. Meyer-Freuler, Triengen, Murhubel. Ein römischer Gutshof im Suretal. Archäologische Schriften Luzern 7 (Luzern 1997).

Flückiger 1941 W. Flückiger, Die römischen Ausgrabungen in Aeschi 1940 - Vorbericht. Jahrb. Solothurn. Gesch. 14, 1941, 173ff..

Flutsch u.a. 1989 L. Flutsch, Campagne de fouilles à Orbe VD-Boscéaz 1988. Bilan provisoire. Jahrb. SGUF 72, 1989, 281ff..

Flutsch u.a. 2002 L. Flutsch / U. Niffeler / F. Rossi, Die Schweiz vom Paläolithikum bis zum frühen Mittelalter. 5. Römische Zeit (Basel 2002).

Francillon u.a. 1983 F. Francillon / D. Weidmann, Photographie aérienne et archéologie vaudoise. Arch. Schweiz 6, 1983, 2ff..

Fuchs 1992 M. Fuchs, Ravalements à Vallon - Les peintures de la villa. Arch. Schweiz 15, 1992, 86ff..

Fuchs 1996 M. Fuchs, Fresques romaines. Trouvailles fribourgeoises. Catalogue d'exposition (Fribourg 1996).

Fuchs 2001 M. Fuchs, La mosaïque de dite de Bacchus et d'Ariane à Vallon. In: Paunier u.a. 2001, 190ff..

Fuchs 2000 M. Fuchs, Vallon. Römische Mosaiken und Museum. Archäologische Führer der Schweiz 31 (Fribourg 2000).

Fuchs u.a. 2002 M. Fuchs / F. Saby, Vallon entre Empire gauloise et 7e siècle. In: Windler u.a. 2002, 59ff..

Furrer 1916 A. Furrer, Die römische Baute in Gretzenbach. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 16, 1914, 187ff..

Gardiol 1990 J.-B. Gardiol, La villa gallo romaine de Vallon FR: suite des recherches. Jahrb. SGUF 73, 1990, 155ff..

Gardiol u.a.1990 J.-B. Gardiol / S. Rebetez / F. Saby, La villa gallo-romaine de Vallon FR. Une seconde mosaïque figurée et un laraire. Arch. Schweiz 13, 1990, 169ff..

Germann u.a. 1957 O. Germann / E. Ettlinger, Untersuchungen am römischen Gutshof Seeb bei Bülach. Jahrb. SGU 46, 1957, 59ff..

Gersbach 1958 E. Gersbach, Die Badeanlage des römischen Gutshofes von Oberentfelden im Aargau. Ur-Schweiz 22, 1958, 33ff..

Gerster 1923 A. Gerster, Eine römische Villa in Laufen (Berner Jura). Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 25, 1923, 193ff..

Gerster 1941 A. Gerster, Römische Villa bei Grenchen. Ur-Schweiz 5, 1941, 8ff..

Gerster 1973 A. Gerster, Der römische Gutshof in Seeb: Rekonstruktionsversuche. Helvetia Arch. 4, 1973, 62ff..

Gerster 1976 A. Gerster, Römische und merowingische Funde in Develier. Helvetia Arch. 7, 1976, 30ff..

Gerster 1976a A. Gerster, Ein römisches Ziegellager bei Münchwilen AG. Helvetia Arch. 7, 1976, 112ff..

Gerster 1983 A. Gerster, Die gallo-römische Villenanlage von Vicques. Rekonstruktion einer Archäologischen Arbeit von Alban Gerster (Porrentruy 1983).

Gerster-Giambonini 1978 A. Gerster-Giambonini, Der römische Gutshof im Müschhag bei Laufen. Helvetia Arch. 9, 1978, 2ff..

Glauser u.a. 1996 K. Glauser / M. Ramstein / R. Bacher, Tschugg - Steiacher. Prähistorische Fundschichten und römischer Gutshof. Schriftenreihe der Erziehungsdirektion des Kantons Bern (Bern 1996).

Gessner 1908 A. Gessner, Die römischen Ruinen bei Kirchberg. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 10, 1908, 24ff..

Gonzenbach 1961 V. von Gonzenbach, Die römischen Mosaiken der Schweiz. Monographien zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Schweiz 13 (Basel 1961).

Gonzenbach 1963 V. von Gonzenbach, Die Verbreitung der gestempelten Ziegel der im 1. Jahrhundert n.Chr. in Vindonissa liegenden römischen Truppen. Bonner Jahrb. 163, 1963, 76ff..

Gonzenbach 1974 V. von Gonzenbach, Die römischen Mosaiken von Orbe. Archäologische Führer der Schweiz 4 (Zürich 1974).

Grütter 1963-1964 H. Grütter, Vier Jahre archäologische Betreuung des Nationalstrassenbaus im Kanton Bern. Jahrb. Bern. Hist. Mus. 43-44; 1963-1964, 471ff..

Grütter u.a. 1965-1966 H. Grütter / A. Bruckner, Der Gallo-römische Gutshof auf dem Murain bei Ersigen. Bern. Hist. Mus. 45-46; 1965-1966, 373ff..

Haldimann 1985 M.-A., Marly (Sarine). Les Râpettes. Archéologie fribourgeoise, chronique archéologique 1985, 34ff.

Haldimann u.a. 2001 M.-A. Haldimann / P. André / E. Broillet-Ramjoué / M. Poux, Entre résidence indigène et domus gallo-romaine: le domaine antique du Parc de La Grange (GE). Arch Schweiz 24/4, 2001, 2ff..

Haller von Königsfelden 1812/1817 F. L. Haller von Königsfelden, Helvetien unter den Römern II - Topographie von Helvetien unter den Römern (Bern-Leipzig 1812; 2. verb. Aufl. 1817).

Hartmann 1975 M. Hartmann, Der römische Gutshof von Zofingen. Archäologische Führer der Schweiz 6 (Brugg 1975).

Hartmann 1979 M. Hartmann, Zwei römische Gutshöfe im Bezirk Baden. Badener Neujahrsblätter 54, 1979, 44ff..

Hartmann u.a. 1985 M. Hartmann / H. Weber, Die Römer im Aargau (Aarau-Frankfurt a.M.-Salzburg 1985).

Hartmann u.a. 1989 M. Hartmann / D. Wälchli, Die römische Besiedlung von Frick. Archäologie der Schweiz 12, 1989, 71ff..

Hedinger 1997-1998 B. Hedinger, Zur römischen Epoche im Kanton Zürich. Ber. Kantonsarch. Zürich 15, 1997-1998, 293ff..

Henny 1992 C. Henny, La villa romaine de Commugny. Mémoire d'archéologie provinciale ramaine présenté à l'Université de Lausanne (Lausanne 1992).

Heuberger 1915 S. Heuberger, Grabungen der Gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa im Jahre 1914. I. Teil. Reste einer römischen Villa in Rüfenach. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 17, 1915, 274ff..

Hidber u.a. 1997 A. Hidber / K. Roth-Rubi (Hrsg.), Beiträge zum Bezirk Zurzach in römischer und frühmittelalterlicher Zeit. Separatdruck aus Argovia 108 (Aarau 1997).

Hinz 1970 H. Hinz, Germania Romana III. Römisches Leben auf germanischem Boden. Gymnasium Beihefte 7 (Heidelberg 1970).

Hoek u.a. 2001 F. Hoek / V. Provenzale / Y. Dubois, Der römische Gutshof von Wetzikon-Kempten und seine Wandmalerei. Arch. Schweiz 24/3, 2001, 2ff..

Hofer 1915 P. Hofer, Römische Anlagen bei Ütendorf und Uttigen. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 17, 1915, 19ff..

Horisberger 2002/2003 B. Horisberger, Neue Ausgrabungen im römischen Gutshof von Oberweningen ZH. Jahresheft des Zürcher Unterländer Museumsvereins 32, 2002/2003, 32ff..

Horisberger 2004 B. Horisberger, Der Gutshof in Buchs und die römische Besiedlung im Furttal. Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 37 (Zürich-Egg 2004).

Hüsser 1940 P. Hüsser, Das Römerbad in Zurzach. Argovia 52, 1940, 265ff..

Hufschmid 1983/85 M. Hufschmid, Der römische Gutshof von Oberweningen. Jahresheft des Zürcher Unterländer Museumsvereins 23, 1983/85.

Jahn 1850 A. Jahn, Der Kanton Bern, deutschen Teils, antiquarisch und topographisch beschrieben (Bern-Zürich 1850).

Joos 1985 M. Joos, Die römischen Mosaiken von Munzach. Arch. Schweiz 8, 1985, 86ff..

Juillerat u.a. 1997 C. Juillerat / F. Schifferdecker, Guide archéologique du Jura et du Jura bernois (Porrentruy 1997).

Kapossy 1966 B. Kapossy, Römische Wandmalereien aus Münsingen und Hölstein. Acta Bernensia 4 (Bern 1966).

Kaenel u.a. 1980 H.-M. von Kaenel / M. Pfanner, Tschugg - Römischer Gutshof. Grabung 1977 (Bern 1980).

Katalog Dijon 1990 Musée Archéologique Dijon, Il était un fois la Côte-d'Or. 20 ans de recherches archéologiques (Paris 1990).

Keller 1844 F. Keller, Die römischen Gebäude bei Kloten. Mitt. Ant. Ges. Zürich 1/2, 1844, 1ff..

Keller 1846/1947 F. Keller, Goldschmuck und christliche Symbole gefunden zu Lunnern im Kanton Zürich. Mitt. Ant. Ges. Zürich 3, 1846/1847, 126ff..

Keller 1864 F. Keller, Statistik der römischen Ansiedlungen in der Ostschweiz. Mitt. Ant. Ges. Zürich 15/3 (Zürich 1864).

Kühne u.a. 1983 E. Kühne / S. Menoud, Bösingen. Freiburger Archäologie, Archäologischer Fundbericht 1983, 34ff..

Kunnert 2001 U. Kunnert, Römische Gutshöfe. Zürcher Archäologie 5 (Zurich-Egg 2001).

La Roche 1910 F. La Roche, Römische Villa in Ormalingen. Basler Zeitschr. Gesch. u. Altkde. 9, 1910, 77ff..

La Roche 1940 F. La Roche, Römische Villa Bennwil. Tätigkeitsberichte der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Baselland 11, 1936-1938, 130ff..

Laur-Belart 1925 R. Laur-Belart, Grabungen der Gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa im Jahre 1923. II. Eine römische Villa in Bözen. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 27, 1925, 65ff..

Laur-Belart 1929 R. Laur-Belart, Grabungen der Gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa 1928. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 31, 1929, 92ff..

Laur-Belart 1952 R. Laur-Belart, Der römische Gutshof von Oberentfelden im Aargau. Ur-Schweiz 16, 1952, 9ff..

Laur-Belart u.a.1953 R. Laur-Belart / T. Strübin, Die römische Villa von Munzach bei Liestal. Ur-Schweiz 17, 1953, 1ff..

Lehner 1980 H. Lehner, Ausgrabungen in der Pfarrkirche von Meikirch. Arch. Schweiz 3, 1980, 118.

Lüdin 1984 O. Lüdin, Die archäologischen Untersuchungen in der Kirche ST. Pankratius von Hitzkirch. Helvetia Arch. 219ff..

Maier-Osterwalder 1989 F. B. Maier-Osterwalder, Ein römisches Gebäude bei Lengnau-"Chilstet". Arch. Schweiz 12, 1989, 60ff..

Martin-Kilcher 1980 S. Martin-Kilcher, Die Funde aus dem römischen Gutshof von Laufen-Müschhag. Ein Beitrag zur Siedlungsgeschichte des nordwestschweizerischen Jura (Bern 1980).

Masserey 1988 C. Masserey, Sondages sur le site Bronze final et gallo-romain des Montoyes à Boécourt JU. Jahrb. SGUF 71, 1988, 189f..

Meier 1900 S. Meier, Die römische Anlage im Schalchmatthau, Gemeinde Ob.-Lunkhofen. Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 2, 1900, 246ff..

Mellet 1899 J. Mellet, Les Fouilles de Buy, entre Cheseaux et Morrens (Vaud). Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 1, 1899, 13ff..

Menoud u.a. 1983 S. Menoud / J.-L. Boisaubert / M. Bouyer, Marly-le Grand (Sarine). Les Râpettes. Archéologie fribourgeoise, chronique archéologique 1983, 54ff..

Meyer-Freuler 1988 C. Meyer-Freuler, Die römischen Villen von Hitzkirch und Grossdietwil - ein Beitrag zur römischen Besiedlung im Kanton Luzern. Arch. Schweiz 11, 1988, 79ff..

Mottier 1960/1961 Y. Mottier, Ein neues Ökonomiegebäude des römischen Gutshofes bei Seeb. Jahrb. SGU 48, 1960/1961, 95ff..

Müller-Beck 1957-1958 H. Müller-Beck, Die Notgrabung 1957 im Bereich der römischen Villa auf dem Buchsi bei Köniz. Jahrb. Bern. Hist. Mus. 37-38, 1957-1958, 249ff..

Ott u.a. 1979 E. Ott / H. Kläui / O. Sigg, Die Geschichte der Gemeinde Neftenbach (Neftenbach 1979).

Paccolat 1989 O. Paccolat, Boécourt JU: La villa gallo-romaine des Montoyes. Fouilles 1988. Jahrb. SGUF 72, 1989, 286ff..

Paccolat 1991 O. Paccolat, L'établissement gallo romain de Boécourt, Les Montoyes (JU, Suisse). Cahier d'Archéologie Jurassienne1 (Porrentruy 1991).

Paratte 1994 C.-A. Paratte, Rapport préliminaire sur la campagne de fouille d'Orbe VD-Boscèaz 1993. Jahrb. SGUF 77, 1994, 148ff..

Paratte u.a. 1994 C.-A. Paratte / Y. Dubois, La villa gallo-romaine d'Yvonand VD-Mordagne. Rapport préliminaire. Jahrb. SGUF 77, 1994, 143ff..

Paunier 1981 D. Paunier, La céramique gallo-romaine de Genève (Genève-Paris 1981).

Paunier u.a. 2001 D. Paunier / C. Schmidt (Hrsg.), La mosaïque gréco-romaine VIII. Actes du 8e Colloque international pour l'etude de la mosaïque antique et médiévale - Lausanne, 6-11 octobre 1997. Cahiers d'archéologie Romande 85-86 (Lausanne 2001).

Pavlinec 1992 M. Pavlinec, Zur Datierung römerzeitlicher Fundstellen in der Schweiz. Jahrb. SGUF 75, 117ff..

Peissard 1943-1945 N. Peissard, Archäologische Karte des Kantons Freiburg. Beitr. Heimatkde. Sensebezirk 17, 1943-1945, 4ff..

Peter 1995 C. Peter, La villa gallo-romain de Buix dans la vallée de l'Allaine (JU). Arch. Schweiz 18, 1995, 25ff..

Poget 1934 S.W. Poget, L'Urba romaine. Aper u général. Rev. Hist. Vaudoise 42, 1934, 257ff..

Primas u.a. 1992 M. Primas / P. Della Casa / B. Schmid-Sikimić, Archäologie zwischen Vierwaldstättersee und Gotthard. Siedlungen und Funde der ur- und frühgeschichtlichen Epochen. Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie 12 (Bonn 1992).

Quiquerez 1844 A. Quiquerez, Notice historique sur quelques monuments de l'ancien Evêché de Bâle. Mitteilungen der Antiquarischen Gesellschaft Zürich 2, 1844, 85f..

Quiquerez 1862 A. Quiquerez, Le Mont-Terrible (Porrentruy 1862).

Ramstein 1998 M. Ramstein, Worb - Sunnhalde. Ein römischer Gutshof im 3. Jahrhundert (Bern 1998).

Rapin 1982 C. Rapin, Villas romaines de environs de Lausanne. Etudes de Lettres, Université de Lausanne No 1, 1982, 29ff..

Rebetez 1992 S. Rebetez, Zwei figürlich verzierte Mosaiken und ein Lararium aus Vallon (Schweiz) - Les deux mosaïques figurées et le laraire de Vallon (Suisse). Antike Welt 23, 1992, 3ff..

Reymond 2001 S. Reymond / E. Broillet-Ramjoué, La villa romaine de Pully et ses peintures murales. Guides archéologiques de la Suisse 32 (Pully 2001).

Ribaux u.a. 1984 Ph. Ribaux / G. De Boe, La villa de Colombier. Fouilles récentes et nouvelle évaluation. Arch. Schweiz 7, 1984, 79ff..

Robert-Charrue 1999 C. Robert-Charrue, La Céramique gallo-romain de la villa de Vicques (JU, Suisse). Mémoire de licence, Universités de Neuchâtel et Lausanne (1999).

Rothé 2001 M.-P. Rothé, Le Jura. Carte Archeologique de la Gaule 39 (Paris 2001).

Roth-Rubi 1986 K. Roth-Rubi, Die Villa von Stutheien/Hüttwilen TG. Ein Gutshof der mittleren Kaiserzeit. Antiqua 14 (Basel 1986).

Roth-Rubi 1994 K. Roth-Rubi, Die ländliche Besiedlung und Landwirtschaft im Gebiet der Helvetier (Schweizer Mittelland) während der Kaiserzeit. In: H. Bender / H. Wolf (Hrsg.), Ländliche Besiedlung und Landwirtschaft in den Rhein-Donau-Provinzen des römischen Reiches. Kolloquium Passau 1991. Passauer Universitätsschr. Arch. 2 (Espelkamp 1994) 309ff..

Roth-Rubi 1987 K. Roth-Rubi / U. Ruoff., Die römische Villa im Loogarten, Zürich-Altstetten - Wiederaufbau vor 260 n.Chr.? Jahrb. SGUF 70, 1987, 145ff..

Roth-Rubi u.a.1992 K. Roth-Rubi / D. Hintermann, Birmenstorf AG, Huggebüel: Archäologische Funde noch einmal betrachtet. Jahresber. Ges. Pro Vindonissa 1992, 25ff..

Russenberger 2001 C. Russenberger, Siedlungsbilder der Blütezeit. In: A. Furger / C. Isler-Kerényi / S. Jacomet / C. Russenberger / J. Schibler, Die Schweiz zur Zeit der Römer. Multikulturelles Kräftespiel vom 1. bis 5. Jahrhundert. Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte der Schweiz 3 (Zürich 2001) 131ff..

Rychener 1990 J. Rychener, Der römerzeitliche Gutshof von Neftenbach ZH - Steinmöri. Arch. Schweiz 13, 1990, 124ff..

Rychener 1999 J. Rychener, Der römische Gutshof in Neftenbach. Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 31 (Zürich-Egg 1999).

Saby 1995 F. Saby, Marly (Sarine). Les Râpettes. Archéologie fribourgeoise, chronique archéologique 1995, 48ff..

Saby 2001 F. Saby, La mosaïque de la Venatio de Vallon et son système d'évacuation d'eau. In: Paunier u.a. 2001, 328ff..

Scherer 1916 P. E. Scherer, Die römische Niederlassung in Alpnachdorf. Mitt. Ant. Ges. Zürich 27/4, 1916, 227ff..

Schnyder 1916 W. Schnyder, Die römische Siedlung auf dem Murhubel bei Triengen, Kanton Luzern. Geschichtsfreund 71, 1916, 259ff..

Schucany 1986 C. Schucany, Der römische Gutshof von Biberist-Spatalhof. Ein Vorbericht. Jahrb. SGUF 69, 1986, 199ff..

Schucany 1999 C. Schucany, Solothurn und Olten - Zwei Kleinstädte und ihr Hinterland in römischer Zeit. Arch. Schweiz 22, 1999, 88ff..

Schuler u.a. 1984 H. Schuler / W. E. Stöckli, Die römische Villa auf dem Niderfeld in Wiedlisbach. Jahrb. Oberaargau 1984, 197ff..

Schwab 1981 H. Schwab, N12 und Archäologie: Archäologische Untersuchungen auf der N12 im Kt. Freiburg 1981, 28ff..

Spitale 1992 D. Spitale, Les monnaies de la villa gallo-romaine de Vicques. Actes de la Société jurassienne d'Emulation 95, 1992, 9ff..

Spycher 1976 H. Spycher, Die Ausgrabungen auf den Nationalstrassen im Kanton Freiburg 1975. Mittbl. SGUF 25/26, 1976, 34ff..

Spycher 1981 H. Spycher, Die Ausgrabungen von Langendorf-Kronmatt 1980. Arch. Schweiz 4, 1981, 62ff..

Spycher 1981a H. Spycher, Ein römisches Gebäude in Langendorf. Arch. Solothurn 2, 1981, 21ff..

Strübin 1956 T. Strübin, Monciacum. Der römische Gutshof und das mittelalterliche Dorf Munzach bei Liestal. Bildbericht über die Ausgrabungen in Munzach 1950-1955. Baselbieter Heimatblätter 20, 1956, 386ff..

Suter u.a. 1986 T. Suter / E. Suter, Römische Villa Chilstet, Lengnau AG, Sondiergrabung 1985. Jahresschrift der Historischen Vereinigung des Bezirks Zurzach Nr. 17, 1986, 1ff..

Suter u.a. 1990 P. J. Suter / F. E. Koenig, Das hangseitige Ökonomiegebäude des römischen Gutshofes Tschugg-Steiacher. Arch. Bern 1, 1990, 157ff..

Suter u.a. 2004 P. J. Suter / M. Ramstein (Red.), Meikirch: Villa romana, Gräber und Kirche. Schriftenreihe der Erziehungsdirektion des Kantons Bern (Bern 2004).

Tatarinoff 1908 E. Tatarinoff, Das römische Gebäude bei Niedergösgen (Solothurn). Anz. Schweizer. Altkde. 10, 1908, 111-123; 213-223.

Terrier 2002 J. Terrier, Découvertes archéologiques dans le canton de Genève en 2000 et 2001. Genava 50, 2002, 355ff..

Viollier 1927 D. Viollier, Carte archéologique du Canton de Vaud (Lausanne 1927).

Vischer 1852 W. Vischer, Eine römische Niederlassung in Frick im Canton Aargau. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Vaterländische Altertümer Basel 4, 1852, 31ff..

Vouga 1943 D. Vouga, Préhistoire du pays de Neuchâtel des origine aux France (Neuchâtel 1943).

Wavre 1905 W. Wavre, Ruines romaines à Colombier. Nusée Neuchâtelois 1905, 153ff..

Weidmann 1978 D. Weidmann, L'établissement romain d'Orbe/Boscéaz. Arch. Schweiz 1, 1978, 84ff..

Weidmann 1978a D. Weidmann, La villa romaine du Prieuré à Pully. Arch. Schweiz 1, 1978, 87ff..

Wiedemer 1965 H.-R. Wiedemer, Römer und Alemannen in der Gegend des Sisselnfeldes. Roche-Zeitung 1965-1, 16ff..

Windler u.a. 2002 R. Windler / M. Fuchs (Hrsg.), De l'Antiquité tardive au Haut Moyen-Âge (300-800) - Kontinuität und Neubeginn. Antiqua 35 (Basel 2002).

The northern and central parts of the province of Germania Superior were dominated by the extensive ranges of the German and French central hill country, including the Rheinischen Schiefergebirges (consisting of the Südeifel, Hunsrück, Rheinischer Westerwald and Taunus), the Pfälzer Wald, the Vosges, the Odenwald, Black Forest and the Swabian Alb. These are split by numerous river valleys, i.a the Rhine, the Moselle, the Nahe, the Glan and, beyond the Rhine, the Main, Neckar, Enz and the Danube. Apart from the higher parts of the river valleys, a series of other natural settlement areas stands out, amongst them the Neuwieder Becken with Pellenz, the Mayener Maifeld, the Wetterau, the hills of Rheinhessen, the Kraichgau and the Neckar basin. All have very fertile soils and are thus excellent starting points for agriculture. The higher parts of the hills, with their poorer soils, were much less suited to farming and were thus less densely settled in the Roman period, or even almost completely avoided. In the following pages, the area on the left bank of the Rhine between the Vinxtbach (between Andernach and Bad Breisig), the province’s northern boundary, and the Südpfalz in the south, plus the area east of the Rhine (the right bank and the Limes hinterland) between the lower Neckar and the Hochrhein, will be treated as case studies for the region.

In the period before the Gallic Wars (58-51BC) the landscapes just described were exclusively settled by Celtic tribes and this is not necessarily contradicted by Julius Caesar’s statement that the Rhine formed the boundary between Gauls and Germans (De bello Gallico I 1, 1-4), as the latter had geopolitical motives. His "Commentarii de bello Gallico" mention remaining Celtic groups on the right bank of the Rhine (De bello Gallico VI 24, 1-3), but it seems that the area west of the Inn and east of the Odenwald may have been largely evacuated just before, or at the start of the War. This is supported by the fact that most settlements and cemeteries stop during the first half of the 1st century (LaTène D1), with the exception of the area north of the Main, which will not be considered here. One of the main reasons behind the abandonment was apparently constant pressure from Elbgermanic tribes from the end of the 2nd century BC. One of the most significant of these incursions was the historically attested occupation attempt by the Suebian Ariovist, between 72 and 58 BC, whose resulting waves of population movement finally initiated the Gallic Wars. The Vangiones, Nemetes and Triboci were apparently part of this incursion, unless we are faced with a much later interpolation into the text (De bello Gallico I 51,2). These tribes were able to settle permanently in Alsace, despites Ariovistus’ defeat near Mulhouse (Alsace) in 58 BC. The exact position of these tribes remains debateable, however, until their controlled settlement by Rome along the left bank of the Rhine from Worms south into Alsace. Even in the early 1st century further re-settlements of Suebian groups are recorded, who may have left Marbodus’ kingdom in Bohemia and settled south of the Main around Starkenburg, along the lower Neckar and around Diersheim (Ortenaukreis/ BW). There is no indication of a large scale resettlement of the abandoned area east of the Rhine before the establishment of Roman rule in the area of the later province, as is apparently confirmed by a statement of P. Cornelius Tacitus (Germania 29): "I do not want to count those people amongst the German tribes, who cultivated the agri decumates, even though they are settling beyond the Rhine and Danube; Gallic riff-raff and desperados claimed this debated area."

Celtic (red) and Germanic

(blue) tribal territories/groups between the Mittel- and Hochrhein around

the mid 1st century BC

|

Celtic (red) and Germanic

(blue) tribal territories/ groups between the Mittel and Hochrhein in

the 1st century AD

|

The situation on the left (western) bank of the Rhine is very different.

The north belonged to the territory of the Treverans who, according to their

material remains, were Celtic-Gallic, and whose territory during the Gallic

Wars included the Ardennes, the Eifel and Hunsrück, and continued north between the Rhein and Maas. Their boundary with the Celtic

Mediomatrici in the south probably ran through Rheinhessen and the Nordpfalz

respectively. The territory of the latter tribe, which stretched west to include

Verdun, originally stopped at the Rhine in the east and bordered the territory

of the Rauraci, Sequani and Leucae in the southeast and south. The establishment

of the military district of Germania Superior at the beginning of the Imperial

period led to the cutting off of the Rhine zone from the core territories of

the Treveri and Mediomatrici, who remained civitates of Gallia Belgica in slightly adjusted form. It is not clear if this division

reflected existing settlement patterns. In the area around Mainz the presence

of the Caerates and Aresaces, who may have been septs of the Treverans, allowed

for possible settlement continuities from the Pre-Roman Iron Age into the Roman

period, while the resettlement of the Vangiones, Nemetes and the Triboki on

the former territory of the Mediomatrici no doubt created a clear break, although,

in the latter case this may ultimately have been caused by the lack of a significant

pre-existing population.

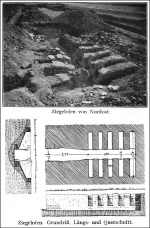

Apart from the oppida, and smaller defended banked enclosures (Ringwallanlagen) whose occupation can stretch into LaTène D2 at reduced levels, all statements concerning the rural population during the 1st century BC (LaTène D1-2) are based on the results from the cemeteries on the left bank of the Rhine, which are have been studied to a greater or lesser extent. Sadly, these can only rarely be associated with known settlement sites. Settlement sites are known, but our current knowledge is largely derived from field walking finds and pit fills found on very limited excavations, and offers little insight into the structure and architecture of the sites. Two of the few exceptions are post-built buildings with wattle walls, found beneath the main residence of the villa "Im Brasil" near Mayen (Kr. Mayen-Koblenz / RLP), and a settlement in Westheim (Kr. Germersheim / RLP), which was defended with a rectangular ditch and a timber and earth rampart.

Late Celtic to early

Roman settlement at Westheim

|

Pre-Roman post-built

structure below the main residence of the villa "Im Brasil" near Mayen

|

The Westheim settlement contained at least five internal buildings and one more outside the defences. These were post-built with nine, twelve or more posts in rectangular ground plans. Occasional doubts have been raised over the late LaTène date assigned to this unusual site, which was found during old excavations, but the buildings correspond closely to late Iron Age structures known elsewhere (e.g. those found in Treveran territory). According to the small finds and the single period structures, the Westheim settlement did not last long after its foundation in the second half of the 1st century AD (LaTène D"). It was abandoned in the late Augustan/ early Tiberian period and no links could be established between it and the small farm, which was built on the site around 70AD. Its finds clearly suggest that the site was inhabited by a Gallo-Celtic population, and it lies on the fringes of an area, where an increased presence of Elbgermanic settlers should be expected from mid-Augustan times. Overall there appears to have been a marked drop in population in the Pfalz (or rather in the area east of the Blies) during the late LaTène period, which was only compensated through the immigration of Germanic groups from the turn of the millennium. Features with Elbgermanic material can often be found in the immediate neighbourhood of later villas, which might suggest possible settlement continuity. In addition to burials, this also occasionally includes settlement remains, which may however consist of little more than occasional post and rubbish pits, as at the villa of Neustadt-Mußbach (Kr. Neustadt a. d. Weinstraße / RLP), which was founded c. 20/30AD, and no buildings can yet be identified or reconstructed. North of the Pfalz the Germanic elements become rarer on cemetery and settlement sites, in favour of indigenous Celtic elements, which already make up the majority at Rheinhessen. Accordingly, we sometimes find evidence of late Iron Age activity next to, or in the vicinity of, Roman farmyards, although so far it has not been possible to prove settlement continuities beyond doubt. Examples such as the villa at Mayen (Kr. Mayen-Koblenz / RLP), whose timber phase may date back to Augustan times, or the villa "Auf der Klosterheck" in Andernach (Kr. Mayen-Koblenz / RLP), which had LaTène period settlement pits and the post holes for an initial timber phase, still provide some of our best evidence.

On the east side of the Rhine (in clear contrast to the situation on the

left bank) no continuities from the original Celtic settlement pattern can

be expected in the Roman period, thanks to massive emigration during LaTène D1. During the second half of the 1st century BC (LaTène D"), partial survival of Celtic groups can only be found on the right bank along

the Hochrhein and the southern Oberrhein valley, where open settlements such

as Breisach-Hochstetten (Kr. Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald / BW) were abandoned

in favour of new defended sites: here Breisach-Münsterberg. There is, however, no information concerning the appearance of the

area’s contemporary farming settlements. The material culture of the newly

arrived German settlers becomes recognisable on the right bank of the Rhine

from the first half of the 1st century AD: particularly south of the lower

Main, along  the lower Neckar and in the Ortenau. However, nothing is known about the appearance

of their buildings either, apart from their settlement refuse. The fact that

at least the Neckar-Suebi (Suebi Nicretes), on the lower Neckar, became a civitas

from the 2nd century after the Roman occupation would, though, suggest that

we should expect some continuity of settlement.

the lower Neckar and in the Ortenau. However, nothing is known about the appearance

of their buildings either, apart from their settlement refuse. The fact that

at least the Neckar-Suebi (Suebi Nicretes), on the lower Neckar, became a civitas

from the 2nd century after the Roman occupation would, though, suggest that

we should expect some continuity of settlement.

One possible example may be the Neckar-Suebian settlement "Ziegelscheuer" in Ladenburg (Rhein-Neckar-Kr. / BW). It was founded in the reign of Claudius and produced the remains of two sunken dwellings. According to the small finds it continued in use at a reduced level, when a villa was built here in the first half of the 2nd century AD. It cannot, however, be established, whether the villa owner and hands originated from the older settlement.

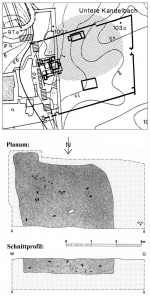

Neckar-Suebian settlement "Ziegelscheuer" in Ladenburg