The two Moesias and Lower Moesia

in particular held an exceptional position among the northern provinces of

the European part of the Empire, traditionally assumed to be Latin-speaking.

The geographical location not very far from the vast, steppe frontier of Europe

and Asia was responsible for this specificity, but not as much as the Greek

cultural component, which had been present in the area for some centuries before

that. It resulted in a linguistic border between Latin and Greek appearing

at some point in the northern Balkans and figured prominently in the urban

development which accompanied the Romanization of Europe and which was an obvious

outcome of the already protracted presence of Greek colonies in the Black Sea littoral. Other factors determining the complexity of the ethnic, cultural and language situation in the two Moesias included:

The two Moesias and Lower Moesia

in particular held an exceptional position among the northern provinces of

the European part of the Empire, traditionally assumed to be Latin-speaking.

The geographical location not very far from the vast, steppe frontier of Europe

and Asia was responsible for this specificity, but not as much as the Greek

cultural component, which had been present in the area for some centuries before

that. It resulted in a linguistic border between Latin and Greek appearing

at some point in the northern Balkans and figured prominently in the urban

development which accompanied the Romanization of Europe and which was an obvious

outcome of the already protracted presence of Greek colonies in the Black Sea littoral. Other factors determining the complexity of the ethnic, cultural and language situation in the two Moesias included:

![]() - factors typical of all the border regions

of the Empire, such as the extensive military presence on the Danubian limes and the role of the province administration;

- factors typical of all the border regions

of the Empire, such as the extensive military presence on the Danubian limes and the role of the province administration;

- resettlement on an unmatched scale of population groups from outside the Empire as well as within its boundaries;

- colonization of the countryside;

- strong Thracian nationalism.

Inscriptions constitute the chief

source for reconstructing the importance and role of Greek and Latin in the

Moesian provinces; therefore, mapping of textual finds in the two languages

illustrates the geographical extent of Greek- and Latin-language epigraphic

culture in the first place and only afterwards, reservations notwithstanding,

the zones where either one or the other was the primary spoken language. Official

inscriptions are not always reliable in establishing these language zones.

One example are the Latin texts on boundary stones (termini) set up still in the 1st century AD in a strongly Greek- and Thracian-speaking

environment between the territory of Odessos and Thrace. Analogous boundary stones erected in AD 136 between the tribal territories of the Thracians and Moesians in the central

part of the Danubian Plain were also in Latin. Neither is the distribution

of religious dedications diagnostic in any way, especially with regard to Lower Moesia.

Inscriptions constitute the chief

source for reconstructing the importance and role of Greek and Latin in the

Moesian provinces; therefore, mapping of textual finds in the two languages

illustrates the geographical extent of Greek- and Latin-language epigraphic

culture in the first place and only afterwards, reservations notwithstanding,

the zones where either one or the other was the primary spoken language. Official

inscriptions are not always reliable in establishing these language zones.

One example are the Latin texts on boundary stones (termini) set up still in the 1st century AD in a strongly Greek- and Thracian-speaking

environment between the territory of Odessos and Thrace. Analogous boundary stones erected in AD 136 between the tribal territories of the Thracians and Moesians in the central

part of the Danubian Plain were also in Latin. Neither is the distribution

of religious dedications diagnostic in any way, especially with regard to Lower Moesia.

In the face of no written application

of local languages, Greek was the language of liturgy over large expanses of

the region. According to B. Gerow’s count, all the votive inscriptions dedicated

by individuals with purely Thracian names were edited in Greek, dedications

erected by Romanized Thracians and persons of Eastern or Greek origin were

mostly in Greek (respectively 63 and 65%) and close to a third of such texts

featuring Roman names could be in Greek as well. In the 2nd century, Hellenized

Thracian priests arriving from the south, that is, from Thrace located just

south of the Stara Planina mountains, appear to have taken relatively quickly

a strong hold of

In the face of no written application

of local languages, Greek was the language of liturgy over large expanses of

the region. According to B. Gerow’s count, all the votive inscriptions dedicated

by individuals with purely Thracian names were edited in Greek, dedications

erected by Romanized Thracians and persons of Eastern or Greek origin were

mostly in Greek (respectively 63 and 65%) and close to a third of such texts

featuring Roman names could be in Greek as well. In the 2nd century, Hellenized

Thracian priests arriving from the south, that is, from Thrace located just

south of the Stara Planina mountains, appear to have taken relatively quickly

a strong hold of  Thracian sanctuaries. Greek votive inscriptions, however, are recorded not only in the Greek towns

on the Black Sea and in Trajanic foundations on the Greek model (Nicopolis

ad Istrum and Marcianopolis), as well as in Thracian sanctuaries and in rural

regions far from the main roads. Isolated examples can be found also in the

limes hinterland (mithreum in Kreta near Oescus and Kozlovec near Novae), and

even in Latin-dominated Novae and the Roman colonies of Scupi and Oescus. Menander’s

comedies were known in the original in these two colonies, as evidenced by

a Latin funerary inscription from Scupi with a quote from Dis eksapaton added in Greek and the title of the Achaioi appearing on a figural mosaic from Oescus.

Thracian sanctuaries. Greek votive inscriptions, however, are recorded not only in the Greek towns

on the Black Sea and in Trajanic foundations on the Greek model (Nicopolis

ad Istrum and Marcianopolis), as well as in Thracian sanctuaries and in rural

regions far from the main roads. Isolated examples can be found also in the

limes hinterland (mithreum in Kreta near Oescus and Kozlovec near Novae), and

even in Latin-dominated Novae and the Roman colonies of Scupi and Oescus. Menander’s

comedies were known in the original in these two colonies, as evidenced by

a Latin funerary inscription from Scupi with a quote from Dis eksapaton added in Greek and the title of the Achaioi appearing on a figural mosaic from Oescus.

Consequently, the distribution of finds of funerary inscriptions is of greater reliability many a time for a study of this issue and we are also aided by a mapping of the occurrence of names of different origins.

Until the early 2nd century AD, meaning

the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, there does not seem to have been any linguistic

frontier to speak off, although the picture may be biased due to the relative

rareness of surviving inscriptions. On the other hand, the rule of the Antonine

and Severan emperors is replete in epigraphic material, but the complexity

of the situation in their times is also much greater in many respects. While

the linguistic division into Greek-speaking Macedonia and Latin-speaking Upper

Moesia with the Roman veterans’ colony in Scupi (see tombstone of a veteran) established under the Flavians as the main center of Romanization in Dardania

raises little doubts, the tracing of this frontier in the Thracian-Moesian

borderland and near the Greek cities on the Black Sea poses considerable difficulties.

Until the early 2nd century AD, meaning

the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, there does not seem to have been any linguistic

frontier to speak off, although the picture may be biased due to the relative

rareness of surviving inscriptions. On the other hand, the rule of the Antonine

and Severan emperors is replete in epigraphic material, but the complexity

of the situation in their times is also much greater in many respects. While

the linguistic division into Greek-speaking Macedonia and Latin-speaking Upper

Moesia with the Roman veterans’ colony in Scupi (see tombstone of a veteran) established under the Flavians as the main center of Romanization in Dardania

raises little doubts, the tracing of this frontier in the Thracian-Moesian

borderland and near the Greek cities on the Black Sea poses considerable difficulties.

Latin dominance along the Lower Danube, in the military bases, towns and extramural settlements near legionary fortresses and auxiliary forts, is unquestionable for the entire period of Roman rule. The rapid Romanization of this zone in the 1st century AD was due to the army and veterans settling in the region, but also civil colonists originating from Italy. Greek-speaking newcomers appearing with time in ever larger numbers from the Greek-language provinces in the Balkans and the East adopted Latin out of necessity. This was apparently the case of the poorly or not at all Hellenized Thracians (Lai and Bessi) moved to Dobrogea from Thrace, as well as of the Getai resettled from beyond the Danube and the craftsmen and traders flowing into Moesia in more or less unorganized fashion, mainly from the eastern, but sometimes also the western reaches of the Empire.

Attested in this group are, for example,

stonemasons, shoe-makers, fullers, also eye specialists among the physicians.

Latin-speaking veterans were also strongly rooted in the area, having started

to stream in already in the end of the 1st century and settling in the vicinity

of army camps, but also in well watered areas with good quality soils in the

hinterland of the Roman limes, chiefly around the later town of Nicopolis ad

Istrum. The situation continued in the 2nd century with veterans of local origin joining in once local recruitment into the army took on greater importance under

Hadrian and later.

Attested in this group are, for example,

stonemasons, shoe-makers, fullers, also eye specialists among the physicians.

Latin-speaking veterans were also strongly rooted in the area, having started

to stream in already in the end of the 1st century and settling in the vicinity

of army camps, but also in well watered areas with good quality soils in the

hinterland of the Roman limes, chiefly around the later town of Nicopolis ad

Istrum. The situation continued in the 2nd century with veterans of local origin joining in once local recruitment into the army took on greater importance under

Hadrian and later.

Significant changes on the linguistic

map of the Danubian Plain came with the establishment of two cities on the

Greek model, namely, Nicopolis ad Istrum and Marcianopolis; some researchers

even believe this to be proof of a conscious Roman language policy, which in

Trajan’s time was supposed to favor Greek. It may be the reason why both Trajanic

foundations with their extensive rural territories were incorporated into Greek-speaking

Thrace and did not pass into Lower Moesian jurisdiction before the reforms

of Septimius Severus.

On the other hand, the language situation

in the highly Latinized territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum must have differed

considerably. Roman and Thracian names predominate in inscriptions from this

region and Latin is the chief language of funerary texts to the virtual exclusion

of Greek and with only a few bilingual funerary inscriptions on the record. In the category of votive inscriptions, Latin practically matched

Greek in popularity. Rural areas settled largely by veterans were Latin-speaking,

while the town itself was bilingual. Changes of the province border in the

end of the 2nd century did little to change the situation. Typical of the language

status in the area around Nicopolis ad Istrum is a bilingual inscription carved

on a stone standard-bearer used in Emporium Piretensium as a measure for contents. The text presents the officer in Latin (emporiarcha empori Piretensium) but the respective measures are given in Greek (hemeina, ksestes etc.), persuading researchers that the latter was the language of choice in

trade.

On the other hand, the language situation

in the highly Latinized territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum must have differed

considerably. Roman and Thracian names predominate in inscriptions from this

region and Latin is the chief language of funerary texts to the virtual exclusion

of Greek and with only a few bilingual funerary inscriptions on the record. In the category of votive inscriptions, Latin practically matched

Greek in popularity. Rural areas settled largely by veterans were Latin-speaking,

while the town itself was bilingual. Changes of the province border in the

end of the 2nd century did little to change the situation. Typical of the language

status in the area around Nicopolis ad Istrum is a bilingual inscription carved

on a stone standard-bearer used in Emporium Piretensium as a measure for contents. The text presents the officer in Latin (emporiarcha empori Piretensium) but the respective measures are given in Greek (hemeina, ksestes etc.), persuading researchers that the latter was the language of choice in

trade.

In the non-urbanized part of the Moesian

interior, such as the basin of the Upper Ogosta, Iskar and Vit, there are zones

straddling the province border where private inscriptions are edited as much

in Greek as in Latin. Latin religious dedications (cf. marble votive plaque from the sanctuary in Glava Panega on the border between Thrace and Lower Moesia) are almost as numerous as those

in Greek, but Latin tombstones are definitely superior in number.

In the non-urbanized part of the Moesian

interior, such as the basin of the Upper Ogosta, Iskar and Vit, there are zones

straddling the province border where private inscriptions are edited as much

in Greek as in Latin. Latin religious dedications (cf. marble votive plaque from the sanctuary in Glava Panega on the border between Thrace and Lower Moesia) are almost as numerous as those

in Greek, but Latin tombstones are definitely superior in number.

The incorporation of Greek colonies on

the Black Sea into the Roman state, first through subordinating them in the

1st century BC to the governor of Macedonia and later Moesia, did not change

their character of typically Greek poleis, where Greek was the language of choice. In Callatis, for example, only 30 of

260 surviving inscriptions are in Latin and this includes most of the official

records which were occasionally written in both Greek and Latin. If only the

text was not an official document regulating the town’s ‘foreign’ relations

with Rome, then the use of Latin could be construed as a courteous act of the

town authorities toward Rome. The capital town of Tomis proves to be quite

exceptional in this light, but in this case the substantial participation in

the life of the town of Latin speakers, namely, the administration, temporarily

stationed army personnel and permanently settled army veterans must have contributed

significantly. Latin texts constitute a little over 25% of the honorific and

almost half of the religious dedications; as for the more diagnostic funerary

texts, Greek appears on two-thirds of the preserved tombstones (cf. a tombstone

from Tomis ).

The incorporation of Greek colonies on

the Black Sea into the Roman state, first through subordinating them in the

1st century BC to the governor of Macedonia and later Moesia, did not change

their character of typically Greek poleis, where Greek was the language of choice. In Callatis, for example, only 30 of

260 surviving inscriptions are in Latin and this includes most of the official

records which were occasionally written in both Greek and Latin. If only the

text was not an official document regulating the town’s ‘foreign’ relations

with Rome, then the use of Latin could be construed as a courteous act of the

town authorities toward Rome. The capital town of Tomis proves to be quite

exceptional in this light, but in this case the substantial participation in

the life of the town of Latin speakers, namely, the administration, temporarily

stationed army personnel and permanently settled army veterans must have contributed

significantly. Latin texts constitute a little over 25% of the honorific and

almost half of the religious dedications; as for the more diagnostic funerary

texts, Greek appears on two-thirds of the preserved tombstones (cf. a tombstone

from Tomis ).

Significant differences in language status can be observed in the rural territories of Greek towns. Greek definitely predominated in the agrarian hinterlands of Odessos and Dionysopolis, both towns on the southern end of the coast, inhabited by a substantial local Thracian population, but in Dobrogea Latin was spoken on the whole, both in the limes hinterland and in vici located in the countryside of Histria, Tomis and partly Callatis. A few official inscriptions from the region clearly demonstrate the leading role played in local society by groups referring to themselves as cives Romani (Roman citizens) et veterani.

This fairly summary review of the linguistic

situation gives an idea of the spread and varied character of languages used

in different parts of the Moesian provinces. The local toponymy is a veritable

mosaic of languages with Illyrian and Celtic, among others, contributing to

a predominant Latin, Greek and Thracian (lingua Bessica). In the inscriptions, this tremendous variety and local coloring is reflected

in the presence of names

This fairly summary review of the linguistic

situation gives an idea of the spread and varied character of languages used

in different parts of the Moesian provinces. The local toponymy is a veritable

mosaic of languages with Illyrian and Celtic, among others, contributing to

a predominant Latin, Greek and Thracian (lingua Bessica). In the inscriptions, this tremendous variety and local coloring is reflected

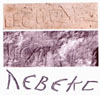

in the presence of names  of different origin (cf. the situation around Nicopolis ad Istrum), spelling and syntax mistakes, mutual borrowing of formulas (e.g. the typical

Latin dedication to the underground deities, Dis Manibus, appears on tombstones quite frequently in Greek translation as Theois Kathachteniois), mutual lexical loanwords, especially of the technical kind used in military

and civil administration (e.g. from Latin to Greek magistratos and kuinkennalis, and from Greek to Latin buleuta and emporium), as well as cases of Latin text being recorded in letters of the Greek alphabet and vice versa. The least errors in Latin texts appear in inscriptions from

the capital towns of Viminacium in Upper Moesia and Tomis in Lower Moesia.

The level of education there should be assumed as being higher than elsewhere.

Yet another regularity comes to mind. The more inscriptions come from a given

area, the smaller the percentage of mistakes in them. Some of the errors in

Latin texts, especially reflecting the phonetic properties of spoken Latin

(e.g. aeres and eres = heres – heir), are proof of the authors’ limited knowledge of the literary tongue.

At the same time, however, their commonplaceness testifies to the common use

of the language in everyday life on most of the Danubian Plain and in some

lands of contemporary Serbia. Finally, Aurelian’s evacuation of Trajanic Dacia

in AD 271, accompanied by resettlement of the strongly Romanized population

of the Dacian provinces south of the Danube, contributed substantially to the

popularity of Latin in this region in Late Antiquity.

of different origin (cf. the situation around Nicopolis ad Istrum), spelling and syntax mistakes, mutual borrowing of formulas (e.g. the typical

Latin dedication to the underground deities, Dis Manibus, appears on tombstones quite frequently in Greek translation as Theois Kathachteniois), mutual lexical loanwords, especially of the technical kind used in military

and civil administration (e.g. from Latin to Greek magistratos and kuinkennalis, and from Greek to Latin buleuta and emporium), as well as cases of Latin text being recorded in letters of the Greek alphabet and vice versa. The least errors in Latin texts appear in inscriptions from

the capital towns of Viminacium in Upper Moesia and Tomis in Lower Moesia.

The level of education there should be assumed as being higher than elsewhere.

Yet another regularity comes to mind. The more inscriptions come from a given

area, the smaller the percentage of mistakes in them. Some of the errors in

Latin texts, especially reflecting the phonetic properties of spoken Latin

(e.g. aeres and eres = heres – heir), are proof of the authors’ limited knowledge of the literary tongue.

At the same time, however, their commonplaceness testifies to the common use

of the language in everyday life on most of the Danubian Plain and in some

lands of contemporary Serbia. Finally, Aurelian’s evacuation of Trajanic Dacia

in AD 271, accompanied by resettlement of the strongly Romanized population

of the Dacian provinces south of the Danube, contributed substantially to the

popularity of Latin in this region in Late Antiquity.

T. Sarnowski

- A. Avram, Inscriptions grecques et latines de Scythie mineure, III. Callatis et son territoire, Bucarest-Paris 1999

- E. Condurachi, La romanizzazione della Dacia e della Scizia Minore, w: Romania Romana, Roma 1974, 63-78

- E. Doruţiu-Boilǎ, Zur Romanisierung der thrakisch-getischen Bevölkerung der Dobrudscha im 1. bis 3. Jh. u.Z. Eine epigraphische Untersuchung, in: Romania Romana, Roma 1974, 281-287

- D. Detschev, Die thrakischen Sprachreste, Wien 1957

- B. Gerov, Romanizmat meždu Dunava I Balkana, čast I, Godišnik na Sofijskija Universitet, Istoriko-Filologičeski Fakultet, 45, 4, 1948/1949; čast II, ibidem, Filologičeski Fakultet 47, 1950/1952 i 48, 1952/1953

- B. Gerov, L’Aspect éthnique et linguistique dans la region entre le Danube et les Balkans à l’époque romaine (Ier-IIIe s.), Studi Urbinati 1-2, 1959, 173-191 (= idem, Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980, 21-39)

- B. Gerov, Das Zusammenleben des Lateinischen und des Griechischen im Ostbalkanraum, w: Neue Beiträge zur Geschichte der alten Welt, II. Römisches Reich, Berlin 1965, 233-242 (= idem, Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980, 239-250)

- B. Gerov, Zur Lesung und Deutung einiger lateinischen Inschriften aus Bulgarien, Godišnik na Sofijskija Universitet, Filologičeski Fakultet 63, 2, 1969, 3-25, (= idem, Beiträge zur Geschichte der römischen Provinzen Moesien und Thrakien. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Amsterdam 1980, 187-209)

- B. Gerov, Die lateinisch-griechische Sprachgrenze auf der Balkanhalbinsel, w: Die Sprachen im Römischen Reich der Kaiserzeit, Beihefte der Bonner Jahrbücher 40, 1980, 147-165

- J. Kaimio, The Romans and the Greek Language, Helsinki 1979

- H. Mihǎescu, Limba latinǎ în provinciile dunǎrene ale Imperiului Roman, Bucureşti 1960

- H. Mihǎescu, La langue latine dans le sud-est de l’Europe, Bucarest 1978

- M. Mirković, Urbanisierung und Romanisierung Obermoesiens, Żiva Antika 19, 2, 1969, 239-262

- M. Mirković, Einheimische Bevölkerung und römische Städte in der Provinz Obermösien, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 6, Berlin-New York 1977, 811 – 848

- A. Mόcsy, Gesellschaft und Romanisation in der römischen Provinz Moesia superior, Budapest 1970

- A. Mόcsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, London 1974

- L. Mrozewicz, Die Romanisierung der Provinz Moesia inferior. Eine Problemskizze, Eos 72, 1984, 375-392

- D.M. Pippidi, La rôle des centres urbains dans le processus de romanisation de la Dacie et de la Scythie Mineure, in: Romania Romana, Roma 1974, 7-27

- A.G. Poulter, Nicopolis ad Istrum. The Anatomy of a Graeco-Roman City, in: Die römische Stadt im 2. Jahrhundert n.Chr. Der Funktionswandel des öffentlichen Raumes, Köln 1992, 69-86

- S. Stati, Limba inscripţiilor latine din Dacia şi Scythia Minor, Bucureşti 1961

- V. Velkov, Dobrudža v perioda na rimskoto vladičestvo (I-III v.), in: A. Fol, S. Dimitrov (eds), Istorija na Dobrudža, I, Sofia 1984, 124-155

- I. Venedikov, Fonetika na latinskite nadpisi ot bǎlgarskite zemi, Izvestija na seminarite pri Istoriko-Filologičeskija Fakultet 1, 1942, 227-245