Roman tombs were – as everywhere else, so also in Pannonia – above ground, and identified at least by a wooden plaque; wealthier families could afford either a tombstone with inscription and portrait of the deceased, or a costly tomb building richly decorated with reliefs.

In contrast to the province of Noricum, where the discovery of the necropolis of Šempeter (near Celeia/Celje, Slovenia) has provided fundamental information for the investigation of the tomb buildings and their reconstruction, in Pannonia no comparable ensemble exists.

It can

be assumed, however, that the same tomb types (funerary stele, funerary altar,

aedicula tomb) as in Noricum also were used here. Along the streets of tombs

which flanked the roads leading out of the settlements, the rectangular or

circular foundations of funerary structures are frequently encountered, as

is the case for example with this one found near the street of tombs at Carnuntum;

the architectural elements, however, are either no longer extant, or are only

preserved as scattered blocks. This situation can be explained

by the fact that, already in antiquity, the buildings fell victim to stone

robbing, as indicated by the frequent re-use of the larger relief blocks as

covering blocks for late antique inhumation burials.

It can

be assumed, however, that the same tomb types (funerary stele, funerary altar,

aedicula tomb) as in Noricum also were used here. Along the streets of tombs

which flanked the roads leading out of the settlements, the rectangular or

circular foundations of funerary structures are frequently encountered, as

is the case for example with this one found near the street of tombs at Carnuntum;

the architectural elements, however, are either no longer extant, or are only

preserved as scattered blocks. This situation can be explained

by the fact that, already in antiquity, the buildings fell victim to stone

robbing, as indicated by the frequent re-use of the larger relief blocks as

covering blocks for late antique inhumation burials.

The Pannonian tomb buildings displayed

representations of the deceased, just as the Norican tombs did. On the majority

of these reliefs, the women wear the indigenous, so-called Norican-Pannonian

fibula costume. The men, on the other hand, relatively early on have themselves

depicted in the toga, provided that they held Roman citizenship. In general, children are represented

in the same manner as their parents. The tomb stone from the parish church

of Neumarkt in Tauchental (Burgenland) can serve as an exmple: here, a husband

and wife are depicted with their daughter. The mother (at the left) and the

daughter (in the middle) wear the native female costume, which is identifiable

by the fibula on the shoulder and the Norican bonnet. The father (at the right)

is dressed in a toga. In his left hand he holds a book scroll, which he touches with the index and

middle fingers of his right hand. This representation can be dated to the mid-Antonine

period on the basis of the hairstyle and beard of the man, which resemble portraits

of the emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161).

The Pannonian tomb buildings displayed

representations of the deceased, just as the Norican tombs did. On the majority

of these reliefs, the women wear the indigenous, so-called Norican-Pannonian

fibula costume. The men, on the other hand, relatively early on have themselves

depicted in the toga, provided that they held Roman citizenship. In general, children are represented

in the same manner as their parents. The tomb stone from the parish church

of Neumarkt in Tauchental (Burgenland) can serve as an exmple: here, a husband

and wife are depicted with their daughter. The mother (at the left) and the

daughter (in the middle) wear the native female costume, which is identifiable

by the fibula on the shoulder and the Norican bonnet. The father (at the right)

is dressed in a toga. In his left hand he holds a book scroll, which he touches with the index and

middle fingers of his right hand. This representation can be dated to the mid-Antonine

period on the basis of the hairstyle and beard of the man, which resemble portraits

of the emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161).

Furthermore, reliefs with the same repertoire

of themes as in Noricum appear as decoration for funerary monuments (see the

chapter ‘Tomb Buildings in Noricum’); however, representations of carriages

and of the funerary banquet are encountered with noticeable frequency in Pannonia.

Furthermore, reliefs with the same repertoire

of themes as in Noricum appear as decoration for funerary monuments (see the

chapter ‘Tomb Buildings in Noricum’); however, representations of carriages

and of the funerary banquet are encountered with noticeable frequency in Pannonia.

Due to the high military presence in Pannonia, military themes were often adopted as content for the design of the side walls; an example from Au in the Leithagebirge (Lower Austria) shows a calo (?) with the equipment of a centurio.

The

described side wall plaques are most frequently encountered in the former heartland

of the civitas Boiorum, that is in the lands beyond Vindobona and Carnuntum. The fact, however,

that these reliefs have generally been found out of their original context

makes a connection to a specific type of tomb building very difficult.

The

described side wall plaques are most frequently encountered in the former heartland

of the civitas Boiorum, that is in the lands beyond Vindobona and Carnuntum. The fact, however,

that these reliefs have generally been found out of their original context

makes a connection to a specific type of tomb building very difficult.

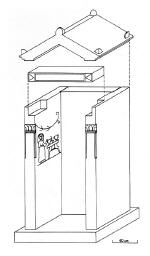

It has been proposed that these plaques

should be reconstructed as part of a tomb aedicula; this proposal,

however, raises the question of why only the inner faces of the plaques, and

not the exterior faces, were carved with reliefs, as tomb aediculas usually

carried reliefs as decoration on all sides.

It has been proposed that these plaques

should be reconstructed as part of a tomb aedicula; this proposal,

however, raises the question of why only the inner faces of the plaques, and

not the exterior faces, were carved with reliefs, as tomb aediculas usually

carried reliefs as decoration on all sides.

This

seeming contradiction has led to the consideration that the reliefs may have

been architectural components of

tumulus tombs. The employment of architectural elements is characteristic for

tumulus tombs of the italo-mediterranean type. We might therefore be dealing

with a sort of tumulus tomb which, in addition to a surrounding wall, also

had an entrance decorated with side wall plaques; furthermore, the application

of a funerary stele between the side plaques beneath the architrave resulted

in the representation of a false door. Such a reconstruction seems

to fulfill the purpose of the plaques better than assigning them to a funerary

aedicula, since by this means only the carved relief side of the plaques would

have been visible. This theory can, however, only be substantiated by the discovery

of such side plaques in situ.

This

seeming contradiction has led to the consideration that the reliefs may have

been architectural components of

tumulus tombs. The employment of architectural elements is characteristic for

tumulus tombs of the italo-mediterranean type. We might therefore be dealing

with a sort of tumulus tomb which, in addition to a surrounding wall, also

had an entrance decorated with side wall plaques; furthermore, the application

of a funerary stele between the side plaques beneath the architrave resulted

in the representation of a false door. Such a reconstruction seems

to fulfill the purpose of the plaques better than assigning them to a funerary

aedicula, since by this means only the carved relief side of the plaques would

have been visible. This theory can, however, only be substantiated by the discovery

of such side plaques in situ.

In conclusion, it can be observed that the design of the funerary monuments fulfilled the desire to be remembered by posterity. For north-west Pannonia, however, many questions still remain unanswered. In spite of the presence of indigenous and local elements, in particular in the design of the reliefs, Roman influence on the character of the tomb cannot be denied. Provided that the theory regarding the architectural components of tumuli is correct, it then follows that the tumuli from the region of the civitas Boiorum reveal a much greater degree of Roman influence than the Norican funerary tumuli, which were composed only of piled up earth without any form of enclosure. One might thereby be able to recognise an attempt to combine local with Roman elements, in order to create a new, independent, local identity.

Julia Stundner

Ch. Ertel – V. Gassner – S- Jilek – H. Stiglitz, Untersuchungen zu den Gräberfeldern in Carnuntum, Der Römische Limes in Österreich 38 (1994)

Ch. Ertel, Grabbauten in Carnuntum, Carnuntum Jahrbuch 1996, 1997, 9 ff.

F. Humer (Hrsg.), Legionsadler und Druidenstab. Vom Legionslager zur Donaumetropole, Sonderausstellung aus Anlass des Jubiläums "2000 Jahre Carnuntum" (Horn 2006) 2 vols.

M. Kronberger, Siedlungschronologische Forschungen zu den canabae legionis von Vindobona. Die Gräberfelder, Monografien der Stadtarchäologie Wien 1 (2005).

M. Mosser, Die Architektur boischer Grabbauten zwischen Wienerwald und Leithagebirge, Fundort Wien 5, 2002, 128 ff.

L. Nagy, Beiträge zur Herkunftsfrage der norischen und pannonischen Hügelgräber, Acta Archaeologica Hungarica 53/4, 2002, 299 ff.

O. H. Urban, Das Gräberfeld von Kapfenstein und die römischen Hügelgräber in Österreich (1984).

O. H. Urban, Der lange Weg zur Geschichte (2002).