grijs.gif

Temples and Shrines

The number of Mediterranean

style classical temples in Britain is few, limited to only eight sites that

are known to possess a substantial example, while a further 11 sites have

smaller examples or have sanctuaries which could be classed as being of classical-type.

The former include Buxton, Lincoln, Wroxeter, London, St Albans, Chichester,

Colchester (associated with the Imperial Cult of the Divine Claudius) and

Bath (the temple to Sulis Minerva), while the latter also include small classical-type

temples from the military vici of the frontier zone (outside the forts of Benwell and Housesteads).

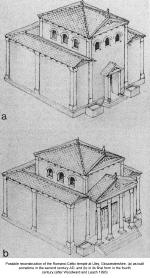

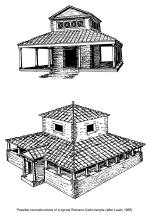

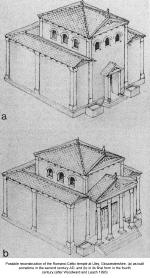

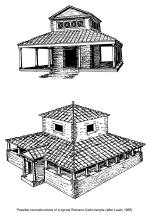

The more common type

of temple in Roman Britain is the Romano-Celtic style temple (fanum), with over fifty examples known. Their distribution has a predominately southern

bias, with concentrations in the south east and the south west being quite

common both in town and country. These were first analysed by R. G. Collingwood

(1930, and 2nd rev. edn. with added material, 1969, 158-60) who describes them as being ‘a

high, square or rectangular shrine surrounded on all sides by a portico or

veranda.’. The inner shrine, or cella, commonly measured between 3.65 and 6.10m square, while the outer wall, which

enclosed the ambulatory measured, externally, between 10.67 and 22.86m square.

The cella would have stood higher than the surrounding enclosure wall and was lighted

from windows high in the walls. The room was not intended to hold a congregation

but was intended to be the focus for the ritual and to house the image of

the god itself. In front of the cella, and within the area of the portico, would have stood the altar, necessary for sacrifices,

along with subsidiary altars, provided by the worshippers, who, as a body,

could be addressed in the enclosure or temenos (Richmond 1955, 12). Simpler forms consist of round, rectangular or polygonal

structures, while the more complex forms comprise concentric rectangular,

polygonal or circular walls, with the inner cella being bounded by a portico of similar shape. The simpler shrines are more common

and are sometimes arranged in groups, such as the major group at the confluence

of sacred springs at Springhead, Kent. Most date to the second or third centuries,

with some rural ones developing later. Sometimes the more complex form occurs

alongside the simpler.

The more common type

of temple in Roman Britain is the Romano-Celtic style temple (fanum), with over fifty examples known. Their distribution has a predominately southern

bias, with concentrations in the south east and the south west being quite

common both in town and country. These were first analysed by R. G. Collingwood

(1930, and 2nd rev. edn. with added material, 1969, 158-60) who describes them as being ‘a

high, square or rectangular shrine surrounded on all sides by a portico or

veranda.’. The inner shrine, or cella, commonly measured between 3.65 and 6.10m square, while the outer wall, which

enclosed the ambulatory measured, externally, between 10.67 and 22.86m square.

The cella would have stood higher than the surrounding enclosure wall and was lighted

from windows high in the walls. The room was not intended to hold a congregation

but was intended to be the focus for the ritual and to house the image of

the god itself. In front of the cella, and within the area of the portico, would have stood the altar, necessary for sacrifices,

along with subsidiary altars, provided by the worshippers, who, as a body,

could be addressed in the enclosure or temenos (Richmond 1955, 12). Simpler forms consist of round, rectangular or polygonal

structures, while the more complex forms comprise concentric rectangular,

polygonal or circular walls, with the inner cella being bounded by a portico of similar shape. The simpler shrines are more common

and are sometimes arranged in groups, such as the major group at the confluence

of sacred springs at Springhead, Kent. Most date to the second or third centuries,

with some rural ones developing later. Sometimes the more complex form occurs

alongside the simpler.

Other temple styles

include basilican temples, with perhaps the best example being the Walbrook mithraeum in London. Some sanctuaries were open-air shrines as Celtic holy places did

not necessarily need a building. A shrine sometimes consisted of just an

area of ground demarcated

by a boundary ditch with perhaps only a sacred tree, statue, or a well. In

the case of Springhead, Kent, there was a free-standing column (Blagg 1979;

Woodfield 1978, 68-9, fig. 5), while at the shrine to the water-deity Coventina,

located close to the fort of Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall, the well or open-basin

took the place of the central cella.

Other temple styles

include basilican temples, with perhaps the best example being the Walbrook mithraeum in London. Some sanctuaries were open-air shrines as Celtic holy places did

not necessarily need a building. A shrine sometimes consisted of just an

area of ground demarcated

by a boundary ditch with perhaps only a sacred tree, statue, or a well. In

the case of Springhead, Kent, there was a free-standing column (Blagg 1979;

Woodfield 1978, 68-9, fig. 5), while at the shrine to the water-deity Coventina,

located close to the fort of Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall, the well or open-basin

took the place of the central cella.

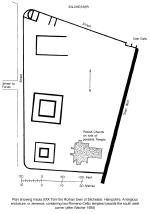

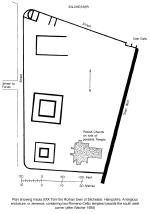

As an example of the

form of sanctuaries within towns, the Roman town of Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum), Hampshire, possessed several temples and some minor shrines, the largest of

which lay in a defined religious enclosure or ‘temple zone’ towards the east

end of the town, known as Insula XXX . This is thought to lie on the site

of an Iron Age precursor, maintaining its religious aspect into the Roman

period. Its importance is reflected in a

street that runs from this enclosure straight to the front of the forum:

the mis-alignment of both to the later town grid suggests that they formed

the earliest components of the town. Towards the west side of this enclose

lay two Romano-Celtic temples. The northern of the two (1) is larger, having

a cella 12.8m square and an external portico 4.1m wide, which also makes it the largest

example known in Britain. The southern temple (2) measured 7.3m square with

a portico of 3.7m in width. The floor of the larger temple was of concrete

which had been raised up by 2.28m above the surrounding ground surface to

form a podium. The smaller temple had a lower podium and the floor was of

red tesserae. The exterior of both was found to have been rendered with red-painted

stucco, while the finding of fragments of Purbeck marble wall-sheathings

and mouldings during the excavation suggested elaborate interior decoration.

Unfortunately no evidence remained regarding the deity worshipped at these

structures, the only religious items found being two miniature clay votive

lamps. Another temple of the same style (3) lay in Insula XXXV. This was

smaller again, with a cella measuring 3.7m by 4.3m and a portico 2.1m wide. Within the cella a platform 0.91m high was found at the western end, presumably to carry statues.

Finds from this temple included three fragments of an inscription mentioning

the association with the temple of a guild of non-townsfolk, collegium peregrinorum, and five fragments of two statues, one of which may represent Mars. A polygonal

temple (4) with sixteen sides, but with a circular cella 10.9m in diameter, lay in Insula VII. It was surrounded by an open enclosure

which probably represented a temenos.

As an example of the

form of sanctuaries within towns, the Roman town of Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum), Hampshire, possessed several temples and some minor shrines, the largest of

which lay in a defined religious enclosure or ‘temple zone’ towards the east

end of the town, known as Insula XXX . This is thought to lie on the site

of an Iron Age precursor, maintaining its religious aspect into the Roman

period. Its importance is reflected in a

street that runs from this enclosure straight to the front of the forum:

the mis-alignment of both to the later town grid suggests that they formed

the earliest components of the town. Towards the west side of this enclose

lay two Romano-Celtic temples. The northern of the two (1) is larger, having

a cella 12.8m square and an external portico 4.1m wide, which also makes it the largest

example known in Britain. The southern temple (2) measured 7.3m square with

a portico of 3.7m in width. The floor of the larger temple was of concrete

which had been raised up by 2.28m above the surrounding ground surface to

form a podium. The smaller temple had a lower podium and the floor was of

red tesserae. The exterior of both was found to have been rendered with red-painted

stucco, while the finding of fragments of Purbeck marble wall-sheathings

and mouldings during the excavation suggested elaborate interior decoration.

Unfortunately no evidence remained regarding the deity worshipped at these

structures, the only religious items found being two miniature clay votive

lamps. Another temple of the same style (3) lay in Insula XXXV. This was

smaller again, with a cella measuring 3.7m by 4.3m and a portico 2.1m wide. Within the cella a platform 0.91m high was found at the western end, presumably to carry statues.

Finds from this temple included three fragments of an inscription mentioning

the association with the temple of a guild of non-townsfolk, collegium peregrinorum, and five fragments of two statues, one of which may represent Mars. A polygonal

temple (4) with sixteen sides, but with a circular cella 10.9m in diameter, lay in Insula VII. It was surrounded by an open enclosure

which probably represented a temenos.

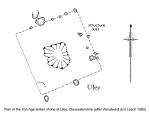

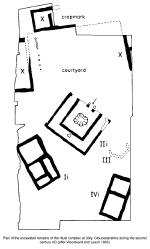

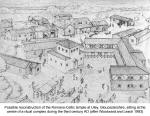

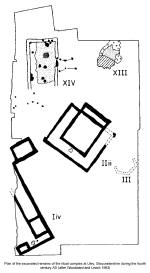

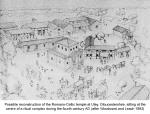

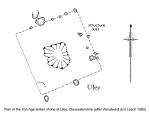

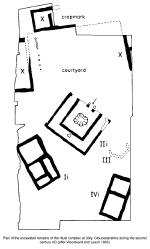

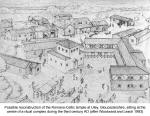

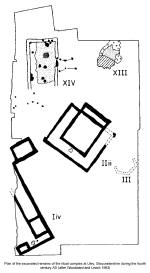

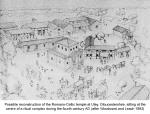

An example of a rural

sanctuary is that found at Uley, Gloucestershire, in the Cotswolds. The sanctuary

there was the site of a nemeton or Celtic sacred place, beginning with a ditched enclosure of possible Neolithic

origin occupying a clearing in a forest. This enclosure may have contained

sacred trees, posts or standing stones but by the late Iron Age a sequence

of timber shrines occupied a central position. Around the early part of the

second century AD this shrine was rebuilt in stone as a style of Romano-Celtic

temple that formed the centre of an area which eventually grew into a substantial

religious complex. There were ancillary buildings housing not just the temple

staff but also visiting worshippers. The first phase of the stone temple

consisted of a

slightly rectangular cella, surrounded by an ambulatory on only three sides. The main entrance, possibly

contained an elaborate classical frontage, was located on the north east

side. Internally, the primary floors did not survive, but a central pit

suggested either a foundation for a plinth to hold the cult statue or the

site of a

ritual water tank. In the later phase the frontage was extended by the addition

of a projecting foundation raised well above ground level and accessed by

a flight of four steps. In reconstruction drawings of the temple the excavators

suggest that this foundation could

have allowed the addition of perhaps four columns and a classical pediment

to the temple frontage.

An example of a rural

sanctuary is that found at Uley, Gloucestershire, in the Cotswolds. The sanctuary

there was the site of a nemeton or Celtic sacred place, beginning with a ditched enclosure of possible Neolithic

origin occupying a clearing in a forest. This enclosure may have contained

sacred trees, posts or standing stones but by the late Iron Age a sequence

of timber shrines occupied a central position. Around the early part of the

second century AD this shrine was rebuilt in stone as a style of Romano-Celtic

temple that formed the centre of an area which eventually grew into a substantial

religious complex. There were ancillary buildings housing not just the temple

staff but also visiting worshippers. The first phase of the stone temple

consisted of a

slightly rectangular cella, surrounded by an ambulatory on only three sides. The main entrance, possibly

contained an elaborate classical frontage, was located on the north east

side. Internally, the primary floors did not survive, but a central pit

suggested either a foundation for a plinth to hold the cult statue or the

site of a

ritual water tank. In the later phase the frontage was extended by the addition

of a projecting foundation raised well above ground level and accessed by

a flight of four steps. In reconstruction drawings of the temple the excavators

suggest that this foundation could

have allowed the addition of perhaps four columns and a classical pediment

to the temple frontage.

Bibliography

Allason-Jones, L. & McKay,

B. (1985) Coventina’s Well. Chester.

Blagg, T. F. C. (1979) ‘The votive column from the Roman temple precinct at Springhead’, Arch. Cant. xcv, 233-9.

Collingwood, R. G. (1930) The Archaeology

of Roman Britain. London.

Collingwood, R. G. & Richmond, I. A. (1969) The

Archaeology of Roman Britain. 2nd rev. edn. London.

Henig, M. (1984) Religion in Roman Britain. London.

Jones, B. & Mattingly,

D. (1990) An Atlas of Roman Britain. London.

Lewis, M. J. T. (1966) Temples

in Roman Britain. Cambridge.

Richmond, I. A. (1955) Roman Britain. London.

Wacher, J. (1995) The

Towns of Roman Britain. 2nd rev. edn.London

Woodfield, P. (1978) ‘Roman Architectural Masonry from Northamptonshire’, Northamptonshire Arch. xiii, 67-86.

Woodward, A & Leach, P. (1993) The

Uley Shrines: Excavation of a ritual complex on West Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire:

1977-9. English Heritage Arch. rep. No. 17. London.

The more common type

of temple in Roman Britain is the Romano-Celtic style temple (fanum), with over fifty examples known. Their distribution has a predominately southern

bias, with concentrations in the south east and the south west being quite

common both in town and country. These were first analysed by R. G. Collingwood

(1930, and 2nd rev. edn. with added material, 1969, 158-60) who describes them as being ‘a

high, square or rectangular shrine surrounded on all sides by a portico or

veranda.’. The inner shrine, or cella, commonly measured between 3.65 and 6.10m square, while the outer wall, which

enclosed the ambulatory measured, externally, between 10.67 and 22.86m square.

The cella would have stood higher than the surrounding enclosure wall and was lighted

from windows high in the walls. The room was not intended to hold a congregation

but was intended to be the focus for the ritual and to house the image of

the god itself. In front of the cella, and within the area of the portico, would have stood the altar, necessary for sacrifices,

along with subsidiary altars, provided by the worshippers, who, as a body,

could be addressed in the enclosure or temenos (Richmond 1955, 12). Simpler forms consist of round, rectangular or polygonal

structures, while the more complex forms comprise concentric rectangular,

polygonal or circular walls, with the inner cella being bounded by a portico of similar shape. The simpler shrines are more common

and are sometimes arranged in groups, such as the major group at the confluence

of sacred springs at Springhead, Kent. Most date to the second or third centuries,

with some rural ones developing later. Sometimes the more complex form occurs

alongside the simpler.

The more common type

of temple in Roman Britain is the Romano-Celtic style temple (fanum), with over fifty examples known. Their distribution has a predominately southern

bias, with concentrations in the south east and the south west being quite

common both in town and country. These were first analysed by R. G. Collingwood

(1930, and 2nd rev. edn. with added material, 1969, 158-60) who describes them as being ‘a

high, square or rectangular shrine surrounded on all sides by a portico or

veranda.’. The inner shrine, or cella, commonly measured between 3.65 and 6.10m square, while the outer wall, which

enclosed the ambulatory measured, externally, between 10.67 and 22.86m square.

The cella would have stood higher than the surrounding enclosure wall and was lighted

from windows high in the walls. The room was not intended to hold a congregation

but was intended to be the focus for the ritual and to house the image of

the god itself. In front of the cella, and within the area of the portico, would have stood the altar, necessary for sacrifices,

along with subsidiary altars, provided by the worshippers, who, as a body,

could be addressed in the enclosure or temenos (Richmond 1955, 12). Simpler forms consist of round, rectangular or polygonal

structures, while the more complex forms comprise concentric rectangular,

polygonal or circular walls, with the inner cella being bounded by a portico of similar shape. The simpler shrines are more common

and are sometimes arranged in groups, such as the major group at the confluence

of sacred springs at Springhead, Kent. Most date to the second or third centuries,

with some rural ones developing later. Sometimes the more complex form occurs

alongside the simpler.